The first line I read when I picked up the New York Times on Wednesday morning, smack in the center of the Dining and Wine section, was in an article by Harold McGee.

"Last week I went to Stanford University to hear a lecture on the molecular biology of smell," he wrote, "and then drove home buzzing with thoughts about what it might mean for people who love to eat."

As I read, standing by my kitchen table in a pair of bright yellow slippers and an old white T-shirt, a dark knob of anxiety immediately began to throb in the pit of my stomach. An immediate, physical reaction to seeing 'smell' and 'eating' in the same sentence, I had to put the paper down and remember to breathe for a moment before I could look at the words again.

The article was not really about smell and its relationship to food—the subject which inspires such a visceral reaction—but was more of an introduction by the author to a column that will appear on occasion in the Dining section of the paper. McGee writes about the science of food and, is known for his book On Food and Cooking, and is highly revered in the culinary world (the Chef for whom I once worked would often say, “In the kitchen, McGee will change your life”).

But with the jolt of that first line, I realized how afraid I have been of knowing more about the effects of my loss of smell. It has been 16 months since I lost the majority of my sense of smell in a car accident and while it was easy to research the immediate effects at the time and write about the day-to-day of recovery ever since, it has become increasingly difficult to look at the long term.

For example, I have been "reading" Diane Ackerman's A Natural History of the Senses, for over six months now. A narrative collection of essays and stories on the five senses, it has been constantly perched on the top of one of the mounds of books in my over-crowded room, 'always next' on the list to be fully tackled. It has accompanied me on many subway and train trips, tucked neatly into my bag with every intention of reading but hardly ever done. It even spent a night flapped open over my face when a late reading attempt brought sleep before I had a chance to either turn off the light or place the book to the side. It begins with a chapter on smell and each time I flipped it open I could feel lines of panic snaking up my legs, stomach, resting in the back of my throat. I always had to put the book down immediately.

The problem for me is that Ackerman writes beautifully and effectively about smell—in language laced simultaneously with poetry and science. She ties smell to pleasure, memory, language, literature, history, sex… all things so intrinsically bound to life. And reading about what I have lost makes it that much more real. If I don’t read the book or the chapter or the article, my subconscious tells me, perhaps I won’t have to face what may potentially be gone.

But after having such an adverse reaction to the Dining section of the paper, generally the best part of Wednesday morning, I decided that enough is enough. I can’t hide from it forever—especially since scent-related writing has been recently getting more attention. Chandler Burr was named the New York Times Perfume Critic; Patrick Suskind’s well-lauded novel Perfume, a book about a murder and a man with an inhuman sense of smell (lying unread, of course, on a pile of books in my room) is soon to come out as a movie; and in last Sunday’s Times Book section there was a review of Luca Turin’s The Secret of Scent, a more scientific look at the theories of olfactory perception and the world of perfume makers. And so Wednesday night after work I sat myself down with Ackerman and fully made my way through the chapter on smell. It wasn’t very hard in the end—perhaps because my sense of smell has been consistently sloughing its way toward recovery (body odor at the gym! toasted almonds at thanksgiving dinner! sautéing garlic from three rooms over!) or, simply, that I have more faith in its future. Its return is a mysterious and interesting phenomenon—one intertwined with all that Ackerman writes of, a delicate reassertion of memory, language, and pleasure. And it’s one that I want to more fully understand.

It’s difficult to write about scent. As Ackerman says, it is the ‘mute’ sense—“…extraordinarily precise, yet it’s almost impossible to describe how something smells to someone who hasn’t smelled it.” Metaphor is ubiquitous—in The Secret of Scent (which arrived on my doorstep from the gods of amazon.com yesterday), for example, Luca Turin describes the scent of a perfume, Nombre Noir, as having the voice “of a child older than its years, at once fresh, husky, modulated and faintly capricious.” And it’s very easy to fall into the chasm of noxious purple prose (“It seems possible that a good few potential readers of The Secret of Scent will send the book windmilling across the room as soon as they encounter Nombre Noir,” says the Times review on Turin’s description). But when done well, the description of a scent can be as transportive as the smell itself. In Swanns Way Proust describes a moment of his day:

I would turn to and fro between the prayer-desk and the stamped velvet armchairs, each one always draped in its crocheted antimacassar, while the fire, baking like a pie the appetizing smells with which the air of the room was thickly clotted, which the dewy and sunny freshness of the morning had already “raised” and started to “set,” puffed them and glazed them and fluted them and swelled them into in invisible though not impalpable country cake, an immense puff-pastry, in which, barely waiting to savor the crustier, more delicate, more respectable, but also drier smells of the cupboard, the chest-of-drawers, and the patterned wall-paper I always returned with an unconfessed gluttony to bury myself in the nondescript resinous, dull, indigestible, and fruity smell of the flowered quilt.

When I read that passage I am immediately there, lost in the scent of Proust’s words. I may have lost the ability to wholly experience my own world of smell. But, in coming to terms with the slow and unsure process of recovery, I’m happy to yet again be able to step into that of others.

Saturday, December 9, 2006

Sunday, November 19, 2006

On Becoming a Muffin

I think that am turning into a muffin.

I think that am turning into a muffin.I baked a plump batch of pumpkin muffins three days ago and now my muffin-consumption frequency has officially reached a dangerous level. In fact, as I made my way out of my apartment last night (after my fourth muffin of the day, yes) I glanced in the mirror and I’m pretty sure I could see the beginning traces of a pumpkin-orange hue emanating from my skin.

I am in the midst of a baking kick. It began a few weeks ago with a dinner party and an almond cake, moved along to bread, some batches of oatmeal cookies, and has now landed in the realm of muffins.

Perhaps this baking spree has something to do with the cooler weather, the encroaching holiday season. I love when my oven is full. And baking, comfort, home – they are all

intertwined.

intertwined.Or perhaps it is more of this anniversary syndrome. One year ago, after all, I was working at the Bakery, hammering out apple pies and chocolate babka in the hectic ambush of Thanksgiving orders. When I got home each night my hands, despite numerous washings, felt constantly encased in a thin film of butter and phyllo dough. My lips always tasted of sugar. Those long hours I spent hunched over a large wood table in the bakery kitchen, carefully tracing lines of colorful frosting onto turkey-shaped sugar cookies are now speaking to my culinary subconscious.

This year I have yet to bake anything resembling a barnyard animal, thankfully, as that would be truly troubling. And despite my initial worry, I believe these vivid orange muffins – light, cakey and moist; with a subtle layer of sweetness – are worth the risk of over-consumption. If you had to transform into some non-human thing, I think that they are an excellent choice. I suppose as a pumpkin muffin you wouldn't be able to turn the pages of the book you're reading, ride a bike in the park, or see over the seat in front of you at the movie theater. But, no matter what, you would be an excellent companion to a steaming mug of ginger tea, a bit of Miles Davis, a rainy evening, and a writing project to complete at my desk.

Pumpkin Muffins

adapted from Gourmet Magazine, November 2006

1 1/2 cups flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 cup canned solid-pack pumpkin

1/3 cup canola oil

2 large eggs

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

1/4 teaspoon allspice

1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

1 cup sugar

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

-Preheat oven to 350 F.

-Whisk together flour and baking powder in a small bowl.

-Whisk together pumpkin, oil, eggs, spices, sugar, baking soda and salt in another, larger bowl. Once smooth, whisk in the flour until just combined.

-Butter a muffin pan and divide the batter evenly into each inlet (should make 12 muffins).

-Bake for 25-30 minutes, until puffed and golden. A toothpick stuck into the center should come out clean.

-Let rest in the pan for five minutes, and then take out the muffins and allow them to cool on a rack until at room temperature.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Bread that Needs no Kneading

The streets were always empty in the chilly pre-dawn hours as I drove to the bakery. The headlights of my car illuminated the street signs, the highway's concrete divider, the brambled bushes lining the back roads. Every morning the radio quietly hummed the news, a metal carafe of coffee steamed in the cup holder by my side, sleep lay heavily in my eyes – I felt as if I were the only one awake.

It was the summer before my freshman year of college and I was working as an assistant pastry chef near my home in suburban Massachusetts. I stumbled into the job not knowing much - my first experience in the professional food world - and left with an ingrained set of culinary skills that have stuck with me ever since. I frost a mean cake, let me tell you.

When I walked into the bakery around 5am each morning, the day’s crop of bread was just emerging from the oven. A result of the night baker's toil, the boxy brown loaves cooled on movable metal shelves until the front doors opened to customers at 7. The muffins and croissants would soon go into the oven, along with the cakes and pastries and scones. The construction of sandwiches and soups was imminent. But at that first moment, right when I arrived and stood talking to the head baker about the day’s work, another cup of coffee cradled in my hands, the room was filled with the scent of pure, unadulterated, overwhelming bread. It was an important part of my daily routine and I loved its warm, sweet aroma - the earthy undertone of yeast. It smelled of the sunlight peeking slowly through the bakery’s window as the day began; the taste of chocolate cake; the feel of puff pastry dough; the fear that lurked constantly in mind with thoughts of my impending college career. It was a scent that made those very early mornings worthwhile – and for a time in my life when I was not so overly food-obsessed and was often out late at night with my high school friends as we shook off those last vestiges of childhood – that says a lot.

When my sense of smell was damaged in the car accident, about 14 months ago now, it was incredibly difficult to come to terms with some of the specific aspects of that loss. The scent of fresh bread being one of them. As my olfactory nerve has healed, certain scents that mean a lot to me have come back with relative haste – rosemary, chocolate, wine – but bread had yet to reemerge.

Yesterday, however, I sat at my kitchen table with a good book (Mark Helprin’s Freddy and Fredericka), a mug of tea (green-ginger), some good music (Elvis Perkins, a recent discovery) and I could not stop sniffing the air. Like a great many others, I had been inspired by a recent recipe in the New York Times: the Sullivan Street Bakery’s no-knead bread. It was in the oven and my apartment smelled like the bakery – sweet, nutty, warm. There was even, perhaps, an undertone of puff pastry and sunlight.

The bread itself was shockingly easy to make. On Friday I had tossed some flour, water, yeast and salt into a bowl. Saturday afternoon I threw it (in a pre-heated, covered, cast iron pot) in the oven. And when I removed the it 50 minutes later, there was a beautiful, crusty brown loaf. I cut myself a large slice (not waiting nearly long enough for it to cool... I have very little patience in matters of tasting freshly baked things), slathered it with butter (Lurpak is delicious) and took a bite. It was damn good. For half of its baking time the bread is sealed in a heavy pot and with the steam amassed, the ending texture is wonderful - crackling crust on the outside, soft and fluffy within.

The bread itself was shockingly easy to make. On Friday I had tossed some flour, water, yeast and salt into a bowl. Saturday afternoon I threw it (in a pre-heated, covered, cast iron pot) in the oven. And when I removed the it 50 minutes later, there was a beautiful, crusty brown loaf. I cut myself a large slice (not waiting nearly long enough for it to cool... I have very little patience in matters of tasting freshly baked things), slathered it with butter (Lurpak is delicious) and took a bite. It was damn good. For half of its baking time the bread is sealed in a heavy pot and with the steam amassed, the ending texture is wonderful - crackling crust on the outside, soft and fluffy within.

The easiest recipe I have ever come across produced some of the best bread to ever exit my oven. The world works in strange ways.

photos above: the final rising of the dough; my oven swallowing the pot of bread as it baked below: bread in a pot; bread in my hand.

***

On another note:

One unseasonably warm day last week, as I walked from my office to the subway in midtown Manhattan, I passed a large pile of trash bags. They were full, stacked on top of each other on the sidewalk, and waiting for the garbage man to take them away. As I maneuvered around them I was suddenly overwhelmed by scent. It took me a moment to recognize what, exactly, I was smelling. (It’s been over a year since my olfactory receptors could register anything unpleasant…) But I stood still for a moment, my nose twitching as I sniffed the air. The stench of rotting trash will probably never again bring such a joyous smile to my lips.

It was the summer before my freshman year of college and I was working as an assistant pastry chef near my home in suburban Massachusetts. I stumbled into the job not knowing much - my first experience in the professional food world - and left with an ingrained set of culinary skills that have stuck with me ever since. I frost a mean cake, let me tell you.

When I walked into the bakery around 5am each morning, the day’s crop of bread was just emerging from the oven. A result of the night baker's toil, the boxy brown loaves cooled on movable metal shelves until the front doors opened to customers at 7. The muffins and croissants would soon go into the oven, along with the cakes and pastries and scones. The construction of sandwiches and soups was imminent. But at that first moment, right when I arrived and stood talking to the head baker about the day’s work, another cup of coffee cradled in my hands, the room was filled with the scent of pure, unadulterated, overwhelming bread. It was an important part of my daily routine and I loved its warm, sweet aroma - the earthy undertone of yeast. It smelled of the sunlight peeking slowly through the bakery’s window as the day began; the taste of chocolate cake; the feel of puff pastry dough; the fear that lurked constantly in mind with thoughts of my impending college career. It was a scent that made those very early mornings worthwhile – and for a time in my life when I was not so overly food-obsessed and was often out late at night with my high school friends as we shook off those last vestiges of childhood – that says a lot.

When my sense of smell was damaged in the car accident, about 14 months ago now, it was incredibly difficult to come to terms with some of the specific aspects of that loss. The scent of fresh bread being one of them. As my olfactory nerve has healed, certain scents that mean a lot to me have come back with relative haste – rosemary, chocolate, wine – but bread had yet to reemerge.

Yesterday, however, I sat at my kitchen table with a good book (Mark Helprin’s Freddy and Fredericka), a mug of tea (green-ginger), some good music (Elvis Perkins, a recent discovery) and I could not stop sniffing the air. Like a great many others, I had been inspired by a recent recipe in the New York Times: the Sullivan Street Bakery’s no-knead bread. It was in the oven and my apartment smelled like the bakery – sweet, nutty, warm. There was even, perhaps, an undertone of puff pastry and sunlight.

The bread itself was shockingly easy to make. On Friday I had tossed some flour, water, yeast and salt into a bowl. Saturday afternoon I threw it (in a pre-heated, covered, cast iron pot) in the oven. And when I removed the it 50 minutes later, there was a beautiful, crusty brown loaf. I cut myself a large slice (not waiting nearly long enough for it to cool... I have very little patience in matters of tasting freshly baked things), slathered it with butter (Lurpak is delicious) and took a bite. It was damn good. For half of its baking time the bread is sealed in a heavy pot and with the steam amassed, the ending texture is wonderful - crackling crust on the outside, soft and fluffy within.

The bread itself was shockingly easy to make. On Friday I had tossed some flour, water, yeast and salt into a bowl. Saturday afternoon I threw it (in a pre-heated, covered, cast iron pot) in the oven. And when I removed the it 50 minutes later, there was a beautiful, crusty brown loaf. I cut myself a large slice (not waiting nearly long enough for it to cool... I have very little patience in matters of tasting freshly baked things), slathered it with butter (Lurpak is delicious) and took a bite. It was damn good. For half of its baking time the bread is sealed in a heavy pot and with the steam amassed, the ending texture is wonderful - crackling crust on the outside, soft and fluffy within.The easiest recipe I have ever come across produced some of the best bread to ever exit my oven. The world works in strange ways.

photos above: the final rising of the dough; my oven swallowing the pot of bread as it baked below: bread in a pot; bread in my hand.

***

On another note:

One unseasonably warm day last week, as I walked from my office to the subway in midtown Manhattan, I passed a large pile of trash bags. They were full, stacked on top of each other on the sidewalk, and waiting for the garbage man to take them away. As I maneuvered around them I was suddenly overwhelmed by scent. It took me a moment to recognize what, exactly, I was smelling. (It’s been over a year since my olfactory receptors could register anything unpleasant…) But I stood still for a moment, my nose twitching as I sniffed the air. The stench of rotting trash will probably never again bring such a joyous smile to my lips.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Nothing Better than a little Chocolate with your Chorizo

On Thursday night I met my friend Becker on the expansive sidewalk outside of a busting Chelsea restaurant, Tia Pol. A well-lauded Spanish tapas establishment, its name immediately jumped to mind when deciding where we should eat - in part through Luisa's recent inspiration, but I have also eaten there once before and knew that in this protracted work week (one that screamed for recompense in the form of good food) Tia Pol would not disappoint.

It didn’t.

Becker and I stood perched in the narrow space between the bar and the brick-studded wall – it is a small restaurant, a long snaking hallway studded with tall tables and a semi-open kitchen to the side – and sipped some Rioja (chosen from their all Spanish wine list) as we waited for a table. The room was dimly lit yet colorful with movement and laughter. We could hardly hear ourselves speak through the din of happy diners.

We were brought to sit, a half hour later, at a small table nestled against the brick siding, across from the kitchen. A highly set window carved into the wall gave the view to an “open" kitchen and throughout the meal I watched a bobbing mop of dark hair and blue and white polka-dotted bandana that belonged, I could only assume, to one of the chefs. Every so often steaming plates of food would pop up onto the window’s ledge, to be quickly whisked off by a waiter or waitress. Alexandra Raij, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, and her husband, Eder Montero, who once worked for Ferran Adria in Barcelona, man the kitchen - a job that they found advertised on craigslist - and now produce Iberian-inspired tapas with high quality ingredients to a constantly flowing crowd.

The service of our own (handsome) waiter was friendly and attentive – a list of specials was spouted glibly, and Becker and I were left to the difficult decision of what to order.

We began with a plate of roasted green peppers – small and posed for one-bite-consumption by holding their dangly long stems - they were browned with heat and covered in olive oil and salt. There were the aceitunas tia pol - black empeltres, manzanillas, arbequinas: bowl of assorted olives, a mottled variation on browns and greens. And pinchos morunos - skewers of succulent pieces of lamb, their flavorful juices absorbed by thick slices of French bread into which they were stuck. The taquitos de atun relleno de boquerones was beautifully plated - a little row of geometrically aligned color - chilled slices of seared tuna, stuffed with marinated white anchovies and topped with what looked like a tiny dollop of olive paste, perhaps, and two small slices of red and green pepper. With concentration we could taste the anchovy – the peppers were overwhelmed by their salt however, and, we thought, could have used some spiciness to round out the flavors.

My favorite, by far, was the chorizo con chocolate – small slices of white bread laden with a melted swipe of thick bittersweet chocolate. Spicy, rich chorizo (a Spanish sausage) was balanced above, topped with a sprinkling of saffron. The flavors combined so surprisingly well that Becker and I had a moment of silence in order to concentrate fully on taste. To top it off we split a warm almond cake – sweet, nutty, and moist.

In the end I was, to say the least, very full. But very happy. And already planning what I will eat the next time around…

It didn’t.

Becker and I stood perched in the narrow space between the bar and the brick-studded wall – it is a small restaurant, a long snaking hallway studded with tall tables and a semi-open kitchen to the side – and sipped some Rioja (chosen from their all Spanish wine list) as we waited for a table. The room was dimly lit yet colorful with movement and laughter. We could hardly hear ourselves speak through the din of happy diners.

We were brought to sit, a half hour later, at a small table nestled against the brick siding, across from the kitchen. A highly set window carved into the wall gave the view to an “open" kitchen and throughout the meal I watched a bobbing mop of dark hair and blue and white polka-dotted bandana that belonged, I could only assume, to one of the chefs. Every so often steaming plates of food would pop up onto the window’s ledge, to be quickly whisked off by a waiter or waitress. Alexandra Raij, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, and her husband, Eder Montero, who once worked for Ferran Adria in Barcelona, man the kitchen - a job that they found advertised on craigslist - and now produce Iberian-inspired tapas with high quality ingredients to a constantly flowing crowd.

The service of our own (handsome) waiter was friendly and attentive – a list of specials was spouted glibly, and Becker and I were left to the difficult decision of what to order.

We began with a plate of roasted green peppers – small and posed for one-bite-consumption by holding their dangly long stems - they were browned with heat and covered in olive oil and salt. There were the aceitunas tia pol - black empeltres, manzanillas, arbequinas: bowl of assorted olives, a mottled variation on browns and greens. And pinchos morunos - skewers of succulent pieces of lamb, their flavorful juices absorbed by thick slices of French bread into which they were stuck. The taquitos de atun relleno de boquerones was beautifully plated - a little row of geometrically aligned color - chilled slices of seared tuna, stuffed with marinated white anchovies and topped with what looked like a tiny dollop of olive paste, perhaps, and two small slices of red and green pepper. With concentration we could taste the anchovy – the peppers were overwhelmed by their salt however, and, we thought, could have used some spiciness to round out the flavors.

My favorite, by far, was the chorizo con chocolate – small slices of white bread laden with a melted swipe of thick bittersweet chocolate. Spicy, rich chorizo (a Spanish sausage) was balanced above, topped with a sprinkling of saffron. The flavors combined so surprisingly well that Becker and I had a moment of silence in order to concentrate fully on taste. To top it off we split a warm almond cake – sweet, nutty, and moist.

In the end I was, to say the least, very full. But very happy. And already planning what I will eat the next time around…

Thursday, November 2, 2006

Balzac's Beets

Last Friday after work I met Jon in Bryant Park and we walked through a cool drizzle to the Museum of Modern Art. It is open late on Fridays, free, and always filled with interesting people to watch.

The statue of Balzac that looms in the front hallway of the museum is an old friend. He is larger than life, a study of thick ridges and cavities. Leaning slightly back, his craggy dark head faces upwards, looking beyond the museumgoers that pass below. Swathed in a robe of cast bronze, his dynamic presence lacks detail but makes up for it with a raw sense of movement. Haughty and thoughtful, he oozes what I have always considered a sensual intellectualism. If it’s possible to have a friend-crush on a hunk of inanimate material, well, then I do.

There is a lot of art – art that I have loved my whole life, art that I concentrated on while studying it in college – that is just so familiar, so often viewed, and so engrained into my visual memory that even their basic color palettes are comforting. Some of it resides in MoMA, much of it does not. Monet’s windblown haystacks… a seductively lounging Tahitian woman of Gauguin’s… a few frank portraits that Cezanne did of his wife… the pointed, mechanical brush-dots of Seurat… a certain Filippino Lippi painting in front of which I spent hours while living in Florence. Auguste Rodin’s Monument to Balzac.

At the museum Jon and I circled around the bronze Balzac for a few minutes; I wanted to say hello. We walked up through the special exhibitions and briefly visited some Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg. It was a short visit, but intimate all the same – like catching up with an old friend over a good cup of coffee.

Afterwards, when hunger and exhaustion pushed us far from any sort of abstract expression, Jon and I emerged from the F train a good ways downtown. It was pouring; I had no umbrella. With my scarf wrapped (a bit grumpily, I’ll admit) around my head, we quickly walked up 2nd Avenue until we arrived at our destination. We landed ourselves at Veselka, Manhattan’s bastion of Ukranian food, and a restaurant that we had been talking about going for a long time. Veselka, after all, is known for its borscht. And for two people who have been known to roast multiple batches of beets on days of searing 90 degree heat in an apartment with no air conditioning, good borscht is something in which to invest some quality time.

We sat at a rickety little table by the window and soon had large bottles of the local (and by local I mean Ukranian) Obolon beer in our hands. When the steaming bowl of vibrant purple soup was plunked down in front of me I shed the last vestiges of my frizzy-haired bad mood. It was thick, rich, and hot – filled with that sweet, earthy beet flavor. A familiar, favorite taste, done right.

In addition, there were the seasonal pumpkin and farmer’s cheese pierogis, Jon’s of hearty ‘Bigos’ stew – consisting mainly of meat (a mixture of kielbasa and pork) with some sauerkraut and onions thrown in the mix (“a substantial meal, fit for a hunter,” the menu said) – and an oozingly sweet apple crumble. The pierogis were a bit bland and the stew a bit too hunter-esque for my taste. But the dessert hit the post-borscht spot just right. In general, everything from the food to the service was homey, low-key and warming.

It was a comforting, familiar evening of art – both fine and culinary. And sitting at the table in the brightly lit corner of Veselka, listening to the rain come sloughing down outside, it seemed fitting when a large, older man stepped into the restaurant, a thick book tucked under his right arm. Swathed in a flowing red robe, his long gray mustache and beard cascaded down the front of his chiseled face. He peered around the room –a haughty yet noble gaze – and I could see a light of recognition when his eyes landed on Jon and me. He moved slowly towards our table, ignoring the raised eyebrows of pink-haired hipsters as they conspicuously judged his outfit. Sitting heavily down at the empty seat to my right the man sighed gruffly, brushing the rain drops off of his shoulder. He glanced haphazardly at the menu and then turned around to catch the eye of our waitress as she walked past. Flipping open her notepad, pen poised, she asked, “What can I get ya?”

And in a stilted, thick French accent, my friend Balzac said, “I’ll have the borscht, please.”

The statue of Balzac that looms in the front hallway of the museum is an old friend. He is larger than life, a study of thick ridges and cavities. Leaning slightly back, his craggy dark head faces upwards, looking beyond the museumgoers that pass below. Swathed in a robe of cast bronze, his dynamic presence lacks detail but makes up for it with a raw sense of movement. Haughty and thoughtful, he oozes what I have always considered a sensual intellectualism. If it’s possible to have a friend-crush on a hunk of inanimate material, well, then I do.

There is a lot of art – art that I have loved my whole life, art that I concentrated on while studying it in college – that is just so familiar, so often viewed, and so engrained into my visual memory that even their basic color palettes are comforting. Some of it resides in MoMA, much of it does not. Monet’s windblown haystacks… a seductively lounging Tahitian woman of Gauguin’s… a few frank portraits that Cezanne did of his wife… the pointed, mechanical brush-dots of Seurat… a certain Filippino Lippi painting in front of which I spent hours while living in Florence. Auguste Rodin’s Monument to Balzac.

At the museum Jon and I circled around the bronze Balzac for a few minutes; I wanted to say hello. We walked up through the special exhibitions and briefly visited some Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg. It was a short visit, but intimate all the same – like catching up with an old friend over a good cup of coffee.

Afterwards, when hunger and exhaustion pushed us far from any sort of abstract expression, Jon and I emerged from the F train a good ways downtown. It was pouring; I had no umbrella. With my scarf wrapped (a bit grumpily, I’ll admit) around my head, we quickly walked up 2nd Avenue until we arrived at our destination. We landed ourselves at Veselka, Manhattan’s bastion of Ukranian food, and a restaurant that we had been talking about going for a long time. Veselka, after all, is known for its borscht. And for two people who have been known to roast multiple batches of beets on days of searing 90 degree heat in an apartment with no air conditioning, good borscht is something in which to invest some quality time.

We sat at a rickety little table by the window and soon had large bottles of the local (and by local I mean Ukranian) Obolon beer in our hands. When the steaming bowl of vibrant purple soup was plunked down in front of me I shed the last vestiges of my frizzy-haired bad mood. It was thick, rich, and hot – filled with that sweet, earthy beet flavor. A familiar, favorite taste, done right.

In addition, there were the seasonal pumpkin and farmer’s cheese pierogis, Jon’s of hearty ‘Bigos’ stew – consisting mainly of meat (a mixture of kielbasa and pork) with some sauerkraut and onions thrown in the mix (“a substantial meal, fit for a hunter,” the menu said) – and an oozingly sweet apple crumble. The pierogis were a bit bland and the stew a bit too hunter-esque for my taste. But the dessert hit the post-borscht spot just right. In general, everything from the food to the service was homey, low-key and warming.

It was a comforting, familiar evening of art – both fine and culinary. And sitting at the table in the brightly lit corner of Veselka, listening to the rain come sloughing down outside, it seemed fitting when a large, older man stepped into the restaurant, a thick book tucked under his right arm. Swathed in a flowing red robe, his long gray mustache and beard cascaded down the front of his chiseled face. He peered around the room –a haughty yet noble gaze – and I could see a light of recognition when his eyes landed on Jon and me. He moved slowly towards our table, ignoring the raised eyebrows of pink-haired hipsters as they conspicuously judged his outfit. Sitting heavily down at the empty seat to my right the man sighed gruffly, brushing the rain drops off of his shoulder. He glanced haphazardly at the menu and then turned around to catch the eye of our waitress as she walked past. Flipping open her notepad, pen poised, she asked, “What can I get ya?”

And in a stilted, thick French accent, my friend Balzac said, “I’ll have the borscht, please.”

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Fall for Osso Buco

There was a cool bite to the air when I walked through Prospect Park on my way to the farmer's market yesterday. The bronze afternoon sunlight fell at a slanted angle, an implication of early darkness. Bright sugar pumpkins and a collection of gnarly gourds were scattered amongst the market's booths of apples and pears, beets and squash. People were wearing scarves and sipping steaming cups of hot cider.

It snuck up on me, but, apparently, it's fall.

There were moments this summer, as I stewed in the claustrophobic heat of my top-floor, un-air-conditioned apartment, when I was positive that fall would never come. I was destined to roast myself into sweaty oblivion forever. How lucky that things change. Sweaters have come out, blankets piled back onto my bed, clunking acorns drop constantly on my fire escape. And it is time to start bringing cold weather cooking back into my repertoire.

Last night, snug in my friend John’s beautiful kitchen, we concocted a magnificent osso buco. The rustic braised veal stew – meltingly tender and full of flavor, topped with a parsley pine-nut gremolata, side-by-side with the traditional Italian accompaniment of a creamy risotto – was the perfect way to inaugurate fall.

Inspired by Mario Batali, the recipe was surprisingly easy. A hefty tomato sauce simmered on the stove as we chopped the onions, carrots, celery and fresh thyme. The veal shanks plopped in a hot pan of olive oil to brown with a dramatic sizzle. Within thirty minutes the osso buco was in the oven, left alone for two and half fragrant hours.

John and I just had to sit back and wait. We watched a movie (something violent with John Cusack, of which I was not a fan), sipped some wine (left over from the cooking), pondered the pros and cons of Leonardo DiCaprio (shockingly good in The Departed, I thought) and the merits and pitfalls of grad-school (is it worth it?).

pros and cons of Leonardo DiCaprio (shockingly good in The Departed, I thought) and the merits and pitfalls of grad-school (is it worth it?).

I eventually removed myself from the couch to stir a leisurely pot of risotto. John’s skills as a Cuisinart master were proven solid when he pulsed together the gremolata garnish. And when I lugged the big pot out of the oven and opened the lid, I was surprised at the ease with which it all came together. (See -- don't I look about to be surprised in that photo?) It is very satisfying to make such a great meal with so little trouble.

I eventually removed myself from the couch to stir a leisurely pot of risotto. John’s skills as a Cuisinart master were proven solid when he pulsed together the gremolata garnish. And when I lugged the big pot out of the oven and opened the lid, I was surprised at the ease with which it all came together. (See -- don't I look about to be surprised in that photo?) It is very satisfying to make such a great meal with so little trouble.

The meat was falling off the bone, a beautiful braise. The risotto was just a bit al dente, the perfect textural foil to the stew. The pine nuts in the gremolata were a necessary crunch; the green of the parsley and yellow of the lemon zest rounded out the color palette.

Fall is coming along quite nicely.

Osso Buco with Pine Nut Gremolata

Inspired by Mario Batali's Molto Italiano

4 3-inch-thick osso buco

salt and pepper

6 tablespoons olive oil

1 carrot, sliced into rounds

1 spanish onion, chopped

1 rib celery, diced

2 tablespoons fresh thyme, chopped

2 cups tomato sauce (recipe below)

2 cups chicken stock

2 cups dry white wine

1/2 cup chopped parsley

1/4 cup toasted pine nuts

zest of one lemon, grated

-preheat oven to 375

-season osso buco with salt and pepper on both sides.

-in a large dutch oven, brown the osso buco in olive oil (the oil should be hot to the point of smoking), on all sides, about 12-15 minutes, and then remove from the pan.

-add carrot, onion, celery, and thyme to the pot and stir for about 10 minutes, until the vegetables are softened.

-add tomato sauce, stock and wine. bring to boil and then place the osso buco back in the pot.

-cover the pot tightly and put into the oven, for 2 to 2 1/2 hours. (the meat will be falling off the bone.)

-make gremolata: mix parsley, pine nuts and lemon zest. give it a few pulses in food processor. sprinkle on top of the osso buco when serving.

Tomato Sauce

1/4 cup olive oil

1 spanish onion, chopped

4 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

3 tablespoons fresh thyme, chopped

1 carrot, chopped

2 28-oz cans whole tomatoes

salt

-heat olive oil, add onion and garlic and cook, stirring, for 8-10 minutes. add thyme and carrot, cook five minutes.

-add tomatoes and bring to a boil. stir often. lower heat and simmer until thick, around 30 minutes.

It snuck up on me, but, apparently, it's fall.

There were moments this summer, as I stewed in the claustrophobic heat of my top-floor, un-air-conditioned apartment, when I was positive that fall would never come. I was destined to roast myself into sweaty oblivion forever. How lucky that things change. Sweaters have come out, blankets piled back onto my bed, clunking acorns drop constantly on my fire escape. And it is time to start bringing cold weather cooking back into my repertoire.

Last night, snug in my friend John’s beautiful kitchen, we concocted a magnificent osso buco. The rustic braised veal stew – meltingly tender and full of flavor, topped with a parsley pine-nut gremolata, side-by-side with the traditional Italian accompaniment of a creamy risotto – was the perfect way to inaugurate fall.

Inspired by Mario Batali, the recipe was surprisingly easy. A hefty tomato sauce simmered on the stove as we chopped the onions, carrots, celery and fresh thyme. The veal shanks plopped in a hot pan of olive oil to brown with a dramatic sizzle. Within thirty minutes the osso buco was in the oven, left alone for two and half fragrant hours.

John and I just had to sit back and wait. We watched a movie (something violent with John Cusack, of which I was not a fan), sipped some wine (left over from the cooking), pondered the

pros and cons of Leonardo DiCaprio (shockingly good in The Departed, I thought) and the merits and pitfalls of grad-school (is it worth it?).

pros and cons of Leonardo DiCaprio (shockingly good in The Departed, I thought) and the merits and pitfalls of grad-school (is it worth it?). I eventually removed myself from the couch to stir a leisurely pot of risotto. John’s skills as a Cuisinart master were proven solid when he pulsed together the gremolata garnish. And when I lugged the big pot out of the oven and opened the lid, I was surprised at the ease with which it all came together. (See -- don't I look about to be surprised in that photo?) It is very satisfying to make such a great meal with so little trouble.

I eventually removed myself from the couch to stir a leisurely pot of risotto. John’s skills as a Cuisinart master were proven solid when he pulsed together the gremolata garnish. And when I lugged the big pot out of the oven and opened the lid, I was surprised at the ease with which it all came together. (See -- don't I look about to be surprised in that photo?) It is very satisfying to make such a great meal with so little trouble.

The meat was falling off the bone, a beautiful braise. The risotto was just a bit al dente, the perfect textural foil to the stew. The pine nuts in the gremolata were a necessary crunch; the green of the parsley and yellow of the lemon zest rounded out the color palette.

Fall is coming along quite nicely.

Osso Buco with Pine Nut Gremolata

Inspired by Mario Batali's Molto Italiano

4 3-inch-thick osso buco

salt and pepper

6 tablespoons olive oil

1 carrot, sliced into rounds

1 spanish onion, chopped

1 rib celery, diced

2 tablespoons fresh thyme, chopped

2 cups tomato sauce (recipe below)

2 cups chicken stock

2 cups dry white wine

1/2 cup chopped parsley

1/4 cup toasted pine nuts

zest of one lemon, grated

-preheat oven to 375

-season osso buco with salt and pepper on both sides.

-in a large dutch oven, brown the osso buco in olive oil (the oil should be hot to the point of smoking), on all sides, about 12-15 minutes, and then remove from the pan.

-add carrot, onion, celery, and thyme to the pot and stir for about 10 minutes, until the vegetables are softened.

-add tomato sauce, stock and wine. bring to boil and then place the osso buco back in the pot.

-cover the pot tightly and put into the oven, for 2 to 2 1/2 hours. (the meat will be falling off the bone.)

-make gremolata: mix parsley, pine nuts and lemon zest. give it a few pulses in food processor. sprinkle on top of the osso buco when serving.

Tomato Sauce

1/4 cup olive oil

1 spanish onion, chopped

4 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

3 tablespoons fresh thyme, chopped

1 carrot, chopped

2 28-oz cans whole tomatoes

salt

-heat olive oil, add onion and garlic and cook, stirring, for 8-10 minutes. add thyme and carrot, cook five minutes.

-add tomatoes and bring to a boil. stir often. lower heat and simmer until thick, around 30 minutes.

Sunday, October 8, 2006

Distractions

On Saturday night of last week I stood over a large metal pot on the stove, steam fogging my glasses, stirring a bubbling cauldron of soup with a wooden spoon. I was wearing baggy sweatpants and an old T-shirt of my brothers, my hair in a frizzy knot on top of my head. The sound of the Gypsy Kings danced in the background of my apartment. For the first time in what felt like a long time, I was staying in for an evening, by myself. I had switched off both my cell phone and computer. I finally had a moment for the kitchen.

Life has been piling up on me the last few weeks and in my much-needed evening of solitude, I was on a mission for comfort. And so I was concocting a simple chickpea-tomato soup – its muted red color was made vibrant by a hefty flavor. The methodical act of chopping the requisite knotty cloves of garlic and sprigs of fresh rosemary released strong scents, a (relatively new) olfactory pleasure that never fails to lift my mood. There is something very healing about the act of cooking alone, just for myself. The mechanics of stirring and chopping, listening to the crackle of onions in a pan, the sensation of steam on my skin are soothing. The time spent alone, concentrating on the stove and the sink, the washing of vegetables and the slow crank of the can opener clears my head.

And in the end when I sat with a good book, a glass of wine, and the quiet lilt of Bach, the warming soup with a hunk of fresh sourdough bread from the farmers market was just what I needed to feel like myself again.

My mind has been in somewhat of a haze in the past month with reverberations of my accident’s anniversary, ending romances, the unexpected death of a friend. And, as a result, I have not felt inspired to write. Even sitting down at my computer today I spent a long time staring blankly at my keyboard, not sure what, if anything, I wanted to write about. I certainly haven’t been cooking; that soup was my first foray into the kitchen in weeks. The act of going out to eat has been more of a tool for distraction, time spent with friends. But of course, that is sometimes the most meaningful.

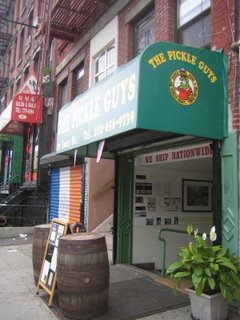

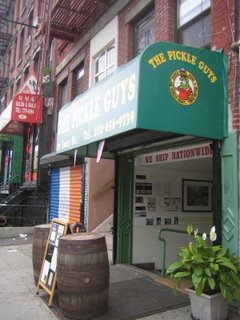

Becca was in New York, unexpectedly, and on a Sunday afternoon we sat in a little French café just a few blocks from my apartment in Park Slope. The end-of-summer light was bright, streaming in the large front window and illuminating our glasses of water on the table. There was a young couple to our left, dressed in stylishly mismatched clothing and chatting with the chef who was obviously a friend. The woman behind the counter drank coffee from a big white mug; flaky brown croissants winked at us from behind the glass. We had spent the morning walking through the nether-regions of Prospect Park and were tired, hungry, in need of caffeine. The day before had been emotionally draining, spent at a funeral in New Jersey. It was difficult to put together any coherent words to express how we were feeling. But we sat and ate warm pressed sandwiches with fresh ricotta, oven roasted tomatoes and basil pesto; side-by-side with small, nutty arugula salads. It was comforting to be there, eating together. We later found ourselves in Manhattan and stumbled onto the magnificent Il Laboratorio del Gelato, a small and eclectic ice cream shop on the Lower East Side. We munched on cones of buttermilk, cinnamon, sour cream and fresh mint ice cream. We enthusiastically pondered the existence of such delicious, unusual flavors as we wandered through a wild little pickle festival on Orchard Street, packed with people and uniquely brined things. Our day of culinary distraction was a welcome, rejuvenating respite from all else.

ourselves in Manhattan and stumbled onto the magnificent Il Laboratorio del Gelato, a small and eclectic ice cream shop on the Lower East Side. We munched on cones of buttermilk, cinnamon, sour cream and fresh mint ice cream. We enthusiastically pondered the existence of such delicious, unusual flavors as we wandered through a wild little pickle festival on Orchard Street, packed with people and uniquely brined things. Our day of culinary distraction was a welcome, rejuvenating respite from all else.

Jon and I, too, have been spanning the boroughs on gourmet expeditions – to a pig roast on the sidewalk in front of Il Buco, fried plantains and empanadas at the Caracas Arepas Bar, spicy pasta puttanesca at a hold-in-the-wall Italian restaurant, quail and coconut pudding at a Brazilian restaurant in Queens. The barbecued chicken and grits in our own neighborhood’s Sadie Mae's was a lengthy and mediocre taste-experience that I would probably not subject myself to again – but the pumpkin ale we brought there from the bodega on the corner was excellent.

The culinary is, obviously, one of my favorite ways to deal with difficult times – but the most meaningful, comforting moment I have had recently involved nothing gourmet.

It happened after seven of my college friends and I stood side-by-side, next to an open grave on a beautiful early-fall morning. It was brisk and sunny; white and red flowers peppered the vibrant green grass in the cemetery surrounding us. The sound of spoken Spanish hardly registered as we listened to the priest; there was only the universal muffle of crying. The red carnation in my hand was cold; the creaking squeal of the coffin as it was lowered into the ground echoed in my fingertips. The eight of us had met our first week of college; the ninth member of that little family was no longer with us.

An hour later we stood together in the wide parking lot of a New Jersey strip mall. The men were in suits, their ties just beginning to loosen around their necks. Becca and I, the only women, were in stark, dark-colored dresses. Many of us had parted ways in the last few years; it was the first time we had all been together in a long time. And we stood together in our fancy, black clothing in a throng of people – men in flip-flops, women in ripped jeans, families with screaming children, gray-haired couples with matching canes – and waited for our names to be called over the loudspeaker. We were waiting for a table at Ihop, The International House of Pancakes. A favorite destination of our friend; we were there together to remember him.

We all squeezed into a booth in the back of the crowded diner and ate soggy pancakes, wilting bacon and coffee poured out of a plastic thermos. I could feel the warmth of the shoulders next to me, the taste of orange juice in my mouth, the slow laughter of my friends as we caught up on days past. And I was struck by the inexplicable fact that we were there, together, and alive. There was something so gut-wrenchingly moving about feeding ourselves together that day. It was the sustenance of companionship and food, together in remembrance of a friend.

Life has been piling up on me the last few weeks and in my much-needed evening of solitude, I was on a mission for comfort. And so I was concocting a simple chickpea-tomato soup – its muted red color was made vibrant by a hefty flavor. The methodical act of chopping the requisite knotty cloves of garlic and sprigs of fresh rosemary released strong scents, a (relatively new) olfactory pleasure that never fails to lift my mood. There is something very healing about the act of cooking alone, just for myself. The mechanics of stirring and chopping, listening to the crackle of onions in a pan, the sensation of steam on my skin are soothing. The time spent alone, concentrating on the stove and the sink, the washing of vegetables and the slow crank of the can opener clears my head.

And in the end when I sat with a good book, a glass of wine, and the quiet lilt of Bach, the warming soup with a hunk of fresh sourdough bread from the farmers market was just what I needed to feel like myself again.

My mind has been in somewhat of a haze in the past month with reverberations of my accident’s anniversary, ending romances, the unexpected death of a friend. And, as a result, I have not felt inspired to write. Even sitting down at my computer today I spent a long time staring blankly at my keyboard, not sure what, if anything, I wanted to write about. I certainly haven’t been cooking; that soup was my first foray into the kitchen in weeks. The act of going out to eat has been more of a tool for distraction, time spent with friends. But of course, that is sometimes the most meaningful.

Becca was in New York, unexpectedly, and on a Sunday afternoon we sat in a little French café just a few blocks from my apartment in Park Slope. The end-of-summer light was bright, streaming in the large front window and illuminating our glasses of water on the table. There was a young couple to our left, dressed in stylishly mismatched clothing and chatting with the chef who was obviously a friend. The woman behind the counter drank coffee from a big white mug; flaky brown croissants winked at us from behind the glass. We had spent the morning walking through the nether-regions of Prospect Park and were tired, hungry, in need of caffeine. The day before had been emotionally draining, spent at a funeral in New Jersey. It was difficult to put together any coherent words to express how we were feeling. But we sat and ate warm pressed sandwiches with fresh ricotta, oven roasted tomatoes and basil pesto; side-by-side with small, nutty arugula salads. It was comforting to be there, eating together. We later found

ourselves in Manhattan and stumbled onto the magnificent Il Laboratorio del Gelato, a small and eclectic ice cream shop on the Lower East Side. We munched on cones of buttermilk, cinnamon, sour cream and fresh mint ice cream. We enthusiastically pondered the existence of such delicious, unusual flavors as we wandered through a wild little pickle festival on Orchard Street, packed with people and uniquely brined things. Our day of culinary distraction was a welcome, rejuvenating respite from all else.

ourselves in Manhattan and stumbled onto the magnificent Il Laboratorio del Gelato, a small and eclectic ice cream shop on the Lower East Side. We munched on cones of buttermilk, cinnamon, sour cream and fresh mint ice cream. We enthusiastically pondered the existence of such delicious, unusual flavors as we wandered through a wild little pickle festival on Orchard Street, packed with people and uniquely brined things. Our day of culinary distraction was a welcome, rejuvenating respite from all else.Jon and I, too, have been spanning the boroughs on gourmet expeditions – to a pig roast on the sidewalk in front of Il Buco, fried plantains and empanadas at the Caracas Arepas Bar, spicy pasta puttanesca at a hold-in-the-wall Italian restaurant, quail and coconut pudding at a Brazilian restaurant in Queens. The barbecued chicken and grits in our own neighborhood’s Sadie Mae's was a lengthy and mediocre taste-experience that I would probably not subject myself to again – but the pumpkin ale we brought there from the bodega on the corner was excellent.

The culinary is, obviously, one of my favorite ways to deal with difficult times – but the most meaningful, comforting moment I have had recently involved nothing gourmet.

It happened after seven of my college friends and I stood side-by-side, next to an open grave on a beautiful early-fall morning. It was brisk and sunny; white and red flowers peppered the vibrant green grass in the cemetery surrounding us. The sound of spoken Spanish hardly registered as we listened to the priest; there was only the universal muffle of crying. The red carnation in my hand was cold; the creaking squeal of the coffin as it was lowered into the ground echoed in my fingertips. The eight of us had met our first week of college; the ninth member of that little family was no longer with us.

An hour later we stood together in the wide parking lot of a New Jersey strip mall. The men were in suits, their ties just beginning to loosen around their necks. Becca and I, the only women, were in stark, dark-colored dresses. Many of us had parted ways in the last few years; it was the first time we had all been together in a long time. And we stood together in our fancy, black clothing in a throng of people – men in flip-flops, women in ripped jeans, families with screaming children, gray-haired couples with matching canes – and waited for our names to be called over the loudspeaker. We were waiting for a table at Ihop, The International House of Pancakes. A favorite destination of our friend; we were there together to remember him.

We all squeezed into a booth in the back of the crowded diner and ate soggy pancakes, wilting bacon and coffee poured out of a plastic thermos. I could feel the warmth of the shoulders next to me, the taste of orange juice in my mouth, the slow laughter of my friends as we caught up on days past. And I was struck by the inexplicable fact that we were there, together, and alive. There was something so gut-wrenchingly moving about feeding ourselves together that day. It was the sustenance of companionship and food, together in remembrance of a friend.

Saturday, September 9, 2006

On an Anniversary

“Anniversary syndrome,” my father told me two weeks ago on the phone, “is a very real thing.” I was walking down 6th avenue, just having left work after a long day, and feeling very ungrounded. “It’s been one year since your accident, Molly,” he said, “And your body remembers these things, even if it’s not conscious. Physically, you remember the pain—and mentally, the trauma. Of course this week will be difficult, it’s only natural.”

As soon as the words came out of his mouth I knew that he was right. Images of myself at the moment of impact had been floating consistently around my mind – much more so than usual. Though often hovering somewhere in my close consciousness, thoughts on the accident—when I was hit by a car early on a Tuesday morning, one of the last days of August, 2005—felt impossibly close. I could not step away from thinking about exactly where I was one year ago—lying in a hospital cot, loopy and acting drunk due to my head trauma; later unable to move from the bed we brought into my family room for a few months, so depressed that I could not look anyone in the eye; hyperventilating in pain when my knee was jostled after surgery; my head spinning, dizzy and unable to focus my eyes; realizing that I had lost my sense of smell.

And it is only now, one year later, that the reality of that past situation is hitting me in full force. That was me. That girl—that depressed, shattered girl—that was me. So it makes sense that the week leading up to August 30th was a bad one, plagued with the constant rumble of unexplained anxiety. Once realized, however, the approaching date of anniversary became infinitely easier to deal with.

And I decided to honor the occasion with the only thing appropriate – a party.

***

Jon and I, yet again, spent a Saturday morning braving the throngs of baby-strollers and nudgy couples laden with plastic bags at the local farmers market. We came home bearing piles of multi-colored heirloom tomatoes, herbs, peppers, berries and plums.

Unpacking our vibrant bounty, Jon examined a handful of fresh green arugula.

“This smells amazing,” he said.

“Give it to me,” I commanded, feeling scentishly bold.

I stuck my head in the green plastic bag and inhaled deeply. Light, peppery wafts registered in my nose. A cool nuttiness. I came up for air, beaming – every new scent brings back waves of sensory images, memories I didn’t even know I had. Jon, on the other hand, was more amused by the sight of my head in a bag, hence the picture.

While planning the party, I played around with different thematic ideas—my favorite being only to serve food-things that I can smell perfectly (a menu of chocolate and wine could not be all bad, if not exactly nutritionally sound) though the thought of decorating the apartment with large plastic-formed noses also appealed. In the end, however, we decided simply to begin with a small dinner gathering, with a great many more friends coming later for a less culinary-oriented party. I didn’t want to revel in what was—I just wanted to have a good time, a simple excuse for friends to come together.

And so in preparation, Jon and I spent the afternoon cooking. Throughout, I’ll admit, there were moments when surges of anxiety came rising from the back of my throat–anxiety that continued to baffle me with its sudden onset. It was still three days before the actual anniversary date. But, in retrospect, I think that imagining myself in the week before the accident was even more difficult than imagining what came next. A year and a few weeks ago I was in Italy with my family—hiking through the gold afternoon light of a Tuscan vineyard, tasting the abundance of blackberries growing on the side of the dirt roads, inhaling the sweet fields of wild lavender, looking forward to my impending travels in France and start date at the Culinary Institute of America. Knowing the shock of what was to come is what really grated against my mind, created bulbous waves of nausea as I stood in my apartment with Jon.

And so in preparation, Jon and I spent the afternoon cooking. Throughout, I’ll admit, there were moments when surges of anxiety came rising from the back of my throat–anxiety that continued to baffle me with its sudden onset. It was still three days before the actual anniversary date. But, in retrospect, I think that imagining myself in the week before the accident was even more difficult than imagining what came next. A year and a few weeks ago I was in Italy with my family—hiking through the gold afternoon light of a Tuscan vineyard, tasting the abundance of blackberries growing on the side of the dirt roads, inhaling the sweet fields of wild lavender, looking forward to my impending travels in France and start date at the Culinary Institute of America. Knowing the shock of what was to come is what really grated against my mind, created bulbous waves of nausea as I stood in my apartment with Jon.

Cooking always helps me to relax, though. It has always been a way to ground myself. And Jon and I certainly can cook. We threw ourselves into the kitchen and created quite a feast: a puff pastry tart constructed with the pile of heirlooms, bright summer quinoa salad, tender lamb roasted on a bed of new potatoes and served with tarragon mustard, a rustic almond-plum buckle.

As we cooked, the scent of rosemary hovered about my head--fresh sprigs were lodged in the lamb as it roasted, perfuming the kitchen. Memory so intrinsically bound in scent, it brought me immediately back to a moment last November. I had been chopping the herb at my mother’s kitchen counter, balancing on my one good leg while my braced left knee dangled useless to the side, when I was suddenly, delightfully assaulted by its rich smell. It was the first scent to come back in full force after I lost that olfactory ability in the accident. And it was the first moment since that day in August that I thought, perhaps, I would be ok. Rosemary smells hopeful to me now.

The afternoon of cooking (pervasive anxiety attacks aside) was indeed a hopeful experience. More and more I find that each time I enter into the kitchen, something has changed.

As I chopped the garlic cloves and sprigs of cilantro for the quinoa salad, their smell burst into my brain in overwhelming waves. The newest of my regained scents, they still surprise me. It takes a while for my olfactory neurons and brain to register and recognize something new. If the source of smell is not right there in front of me I will stand still, breathing deeply and trying to put unattainable words to scent for a long time. The basic smell-related information hovers at the tip of my tongue. I often need someone to define for me what my olfactory neurons have forgotten. The garlic and cilantro on the cutting board beckoned with their familiar, close-to-forgotten smells; I’m happy that they still exist.

And as the heirloom tomato tart and, later, the almond-plum buckle baked in the oven the kitchen was filled with a nutty sweet warmth. Through this experience I have learned of the scent of temperature. Different than a physical measurement or sensation, there is something intrinsically olfactory about it. Try smelling a pot of boiling water; there is something there beyond the heat. It is a soothing, delicate washed perfume.

***

In the end it was a fun evening. There was eating, drinking, friends—an excellent way to celebrate the strange and dramatic turns that I have had this year.

At one point in the night I stood quietly in the sprawling crowd on my roof, and, for just a moment, watched the dappled Manhattan skyline in the distance. I felt calm and relaxed, for the first time all day. Anniversaries can be rough, as this city is clearly coming to terms with itself. I am just happy that I could make something fun come out of an experience that was not.

“If someone had told me last summer where I would be right now,” I thought, looking out at the city, “I don’t think I would have believed them.” It’s been an odd year.

Heirloom Tomato Tart with Capers and Caramelized Onions

adapted from Suzanne Goin's Sunday Suppers at Lucques

3 T extra-virgin olive oil

6 cups thinly sliced onions (1.5 pounds)

1 T thyme leaves

1 T butter (unsalted)

1 sheet frozen all-butter puff pastry, thawed

1 egg yolk

3 medium heirloom tomatoes, mixed colors

2 tsp capers

1/4 c Nicoise olives, pitted, sliced

Heat a large saute pan, add olive oild and then the onions, 2 teaspoons of thyme, 1 teaspoon salt and some pepper.

Cook for about 10 minutes, stirring often.

Turn down the heat to medium, add the butter, and cook for another 15 minutes, continually stirring, until the onions are caramelized and a deep golden brown. Let cool.

Preheat oven to 400F.

Put the defrosted puff pastry on a sheet of parchment paper on a baking pan. Score an 1/8 inch thick border around the sides with a knife. Whisk together the egg yolk with a teaspoon of water and then brush the mixture along the border. Spread the onions within.

Core the tomatoes and slice into 1/4 inch rounds. Place them on top of the onions spread evenly. Season with 1/4 tsp salt and some pepper.

Arrange the capers and olives on top, sprinkle with the remaining thyme.

Bake 10 minutes. Turn the pan around in the oven and bake for another 10-12 minutes, until the crust is a deep golden brown. Serves 8 as a first course.

As soon as the words came out of his mouth I knew that he was right. Images of myself at the moment of impact had been floating consistently around my mind – much more so than usual. Though often hovering somewhere in my close consciousness, thoughts on the accident—when I was hit by a car early on a Tuesday morning, one of the last days of August, 2005—felt impossibly close. I could not step away from thinking about exactly where I was one year ago—lying in a hospital cot, loopy and acting drunk due to my head trauma; later unable to move from the bed we brought into my family room for a few months, so depressed that I could not look anyone in the eye; hyperventilating in pain when my knee was jostled after surgery; my head spinning, dizzy and unable to focus my eyes; realizing that I had lost my sense of smell.

And it is only now, one year later, that the reality of that past situation is hitting me in full force. That was me. That girl—that depressed, shattered girl—that was me. So it makes sense that the week leading up to August 30th was a bad one, plagued with the constant rumble of unexplained anxiety. Once realized, however, the approaching date of anniversary became infinitely easier to deal with.

And I decided to honor the occasion with the only thing appropriate – a party.

***

Jon and I, yet again, spent a Saturday morning braving the throngs of baby-strollers and nudgy couples laden with plastic bags at the local farmers market. We came home bearing piles of multi-colored heirloom tomatoes, herbs, peppers, berries and plums.

Unpacking our vibrant bounty, Jon examined a handful of fresh green arugula.

“This smells amazing,” he said.

“Give it to me,” I commanded, feeling scentishly bold.

I stuck my head in the green plastic bag and inhaled deeply. Light, peppery wafts registered in my nose. A cool nuttiness. I came up for air, beaming – every new scent brings back waves of sensory images, memories I didn’t even know I had. Jon, on the other hand, was more amused by the sight of my head in a bag, hence the picture.

While planning the party, I played around with different thematic ideas—my favorite being only to serve food-things that I can smell perfectly (a menu of chocolate and wine could not be all bad, if not exactly nutritionally sound) though the thought of decorating the apartment with large plastic-formed noses also appealed. In the end, however, we decided simply to begin with a small dinner gathering, with a great many more friends coming later for a less culinary-oriented party. I didn’t want to revel in what was—I just wanted to have a good time, a simple excuse for friends to come together.

And so in preparation, Jon and I spent the afternoon cooking. Throughout, I’ll admit, there were moments when surges of anxiety came rising from the back of my throat–anxiety that continued to baffle me with its sudden onset. It was still three days before the actual anniversary date. But, in retrospect, I think that imagining myself in the week before the accident was even more difficult than imagining what came next. A year and a few weeks ago I was in Italy with my family—hiking through the gold afternoon light of a Tuscan vineyard, tasting the abundance of blackberries growing on the side of the dirt roads, inhaling the sweet fields of wild lavender, looking forward to my impending travels in France and start date at the Culinary Institute of America. Knowing the shock of what was to come is what really grated against my mind, created bulbous waves of nausea as I stood in my apartment with Jon.

And so in preparation, Jon and I spent the afternoon cooking. Throughout, I’ll admit, there were moments when surges of anxiety came rising from the back of my throat–anxiety that continued to baffle me with its sudden onset. It was still three days before the actual anniversary date. But, in retrospect, I think that imagining myself in the week before the accident was even more difficult than imagining what came next. A year and a few weeks ago I was in Italy with my family—hiking through the gold afternoon light of a Tuscan vineyard, tasting the abundance of blackberries growing on the side of the dirt roads, inhaling the sweet fields of wild lavender, looking forward to my impending travels in France and start date at the Culinary Institute of America. Knowing the shock of what was to come is what really grated against my mind, created bulbous waves of nausea as I stood in my apartment with Jon.

Cooking always helps me to relax, though. It has always been a way to ground myself. And Jon and I certainly can cook. We threw ourselves into the kitchen and created quite a feast: a puff pastry tart constructed with the pile of heirlooms, bright summer quinoa salad, tender lamb roasted on a bed of new potatoes and served with tarragon mustard, a rustic almond-plum buckle.

As we cooked, the scent of rosemary hovered about my head--fresh sprigs were lodged in the lamb as it roasted, perfuming the kitchen. Memory so intrinsically bound in scent, it brought me immediately back to a moment last November. I had been chopping the herb at my mother’s kitchen counter, balancing on my one good leg while my braced left knee dangled useless to the side, when I was suddenly, delightfully assaulted by its rich smell. It was the first scent to come back in full force after I lost that olfactory ability in the accident. And it was the first moment since that day in August that I thought, perhaps, I would be ok. Rosemary smells hopeful to me now.

The afternoon of cooking (pervasive anxiety attacks aside) was indeed a hopeful experience. More and more I find that each time I enter into the kitchen, something has changed.

As I chopped the garlic cloves and sprigs of cilantro for the quinoa salad, their smell burst into my brain in overwhelming waves. The newest of my regained scents, they still surprise me. It takes a while for my olfactory neurons and brain to register and recognize something new. If the source of smell is not right there in front of me I will stand still, breathing deeply and trying to put unattainable words to scent for a long time. The basic smell-related information hovers at the tip of my tongue. I often need someone to define for me what my olfactory neurons have forgotten. The garlic and cilantro on the cutting board beckoned with their familiar, close-to-forgotten smells; I’m happy that they still exist.

And as the heirloom tomato tart and, later, the almond-plum buckle baked in the oven the kitchen was filled with a nutty sweet warmth. Through this experience I have learned of the scent of temperature. Different than a physical measurement or sensation, there is something intrinsically olfactory about it. Try smelling a pot of boiling water; there is something there beyond the heat. It is a soothing, delicate washed perfume.

***

In the end it was a fun evening. There was eating, drinking, friends—an excellent way to celebrate the strange and dramatic turns that I have had this year.

At one point in the night I stood quietly in the sprawling crowd on my roof, and, for just a moment, watched the dappled Manhattan skyline in the distance. I felt calm and relaxed, for the first time all day. Anniversaries can be rough, as this city is clearly coming to terms with itself. I am just happy that I could make something fun come out of an experience that was not.

“If someone had told me last summer where I would be right now,” I thought, looking out at the city, “I don’t think I would have believed them.” It’s been an odd year.

Heirloom Tomato Tart with Capers and Caramelized Onions

adapted from Suzanne Goin's Sunday Suppers at Lucques

3 T extra-virgin olive oil

6 cups thinly sliced onions (1.5 pounds)

1 T thyme leaves

1 T butter (unsalted)

1 sheet frozen all-butter puff pastry, thawed

1 egg yolk

3 medium heirloom tomatoes, mixed colors

2 tsp capers

1/4 c Nicoise olives, pitted, sliced

Heat a large saute pan, add olive oild and then the onions, 2 teaspoons of thyme, 1 teaspoon salt and some pepper.

Cook for about 10 minutes, stirring often.

Turn down the heat to medium, add the butter, and cook for another 15 minutes, continually stirring, until the onions are caramelized and a deep golden brown. Let cool.

Preheat oven to 400F.

Put the defrosted puff pastry on a sheet of parchment paper on a baking pan. Score an 1/8 inch thick border around the sides with a knife. Whisk together the egg yolk with a teaspoon of water and then brush the mixture along the border. Spread the onions within.

Core the tomatoes and slice into 1/4 inch rounds. Place them on top of the onions spread evenly. Season with 1/4 tsp salt and some pepper.

Arrange the capers and olives on top, sprinkle with the remaining thyme.

Bake 10 minutes. Turn the pan around in the oven and bake for another 10-12 minutes, until the crust is a deep golden brown. Serves 8 as a first course.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

The Spotted Pig: Infinitely Better than Bad Art

On Wednesday night a work colleague and I stood in the wide expanse of a Chelsea warehouse turned art gallery. There were women dressed in bright, ruffled cocktail dresses and spindly stilettos, men in pressed suit jacket and ties. Shiny, perfectly tussled hair was ubiquitous. Small plastic cups were clutched in hand—sparkling roses and scotch on the rocks. There was an open bar; the line resembled a veritable mosh-pit of thirsty art supporters. The sun was setting and through the large windows we could see fading pink and purple cloud-streaks stretch out over the west river.

It was a charity art event; we were drawn to attend because of its swanky location, the press pass that granted us free entryway and, of course, its overarching good cause. The open bar and promise of food didn’t hurt, either. Once inside, however, it was pretty obvious that we didn’t fit in. We had walked over after work and were wearing jeans and bedraggled button down shirts, carrying bags of books and papers and not entirely sure what we were entering into.

The paintings on the walls were bright swaths of oil and acrylic and looked as if they were painted by an uninspired three-year-old. A chair-deemed-art was perched on a small stand near the window—clear plastic wrapped into an oblong shape and secured with small wire stands, an open hole at the bottom where, I can only imagine, you were supposed to uncomfortably seat yourself. The installation of small plaster donut-esque circles that hung on the wall was… mystifying at best. A beat-poet-turned-rapper was intonating harsh, vulgar lyrics into a microphone while no one listened. There were photographers and a cameraman there to capture the beautiful and the big names; we didn’t recognize anyone.

We positioned ourselves in a comfortable corner and were entertained watching the people and odd happenings around us. Our talk on the artwork nearby increased in decibel and crudeness with each glass of free wine. We were hungry, but the only way to partake in the hors d'oeuvres (because of the large, ravenous crowd) was to stand right next to the kitchen exit-way and practically pounce on the waitresses as they emerged with their loaded food trays. It became clear that this was not the place to stay for two starving, non-fancy people.

We looked at each other, eyebrows raised.

“How about The Spotted Pig?” he asked.

The words were like music to my ears.

“Absolutely perfect,” I said, beaming.

I have wanted to go to The Spotted Pig for a long time now. It is an old style gastro-pub in the West Village, owned by Ken Friedman and April Bloomfield and constructed with considerable help by Mario Batali. April Bloomfield, an English chef, has reinterpreted common bar food and brought it to an exciting, gourmet level. The restaurant/bar is always crowded—with celebrities and commoners alike—and promises some on the most illustrious people watching (Mario Batali himself, it is rumored, spends many a night drinking within its cozy walls til the early morning hours) and great late night food in New York. We immediately hopped in a cab and found ourselves at the door to the restaurant.