Thursday, December 20, 2007

Evening, New York

We stepped into McNulty’s Coffee and Tea Company on Christopher Street. The bronzed wood shop was filled with burlap sacks, glass containers of loose tea, and coffee beans that were so fresh they shone. It smelled thickly of cocoa and coffee. The scent was so rich that the flick of a finger could indent the air.

“You must love to come into work everyday,” said Matt to the man behind the counter, inhaling. “It smells so good.”

The coffee-purveyor smiled as he ground us a pound of “Java Mountain Supreme.”

“We do love it, but not because of the scent. We just can’t smell it anymore,” he said with a quiet laugh. “You get used to anything. One week here and the smell is gone.”

“Oh, sad.”

We left and took a turn through the nutty yellow rounds piled on the shelves and behind the counter of Murray’s Cheese Shop on Bleecker Street. I bought some Marcona almonds in honey and yogurt from Iceland, nestling them between the books in my bag.

Outside and around the corner, a man in a thick brown coat was wrapping a pine tree in mesh for a couple to take home. We walked by the forest-like stack of dark trees leaning against a makeshift wooden fence, some festooned with red ribbons.

I took a deep breath. A new scent.

“Can you smell that?” Matt asked, sticking his face near the pile of pine.

“Yes,” I said, surprised by the sudden and new. “It’s Christmas.”

Later that night I sat in the subway on my way back to Brooklyn. The brown paper parcel of coffee from McNulty’s was in the bag between my feet. I was trying to read my book but I couldn’t concentrate. I was too distracted by the scent of coffee.

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Brooklyn Food Group; Take Four

We had the fourth meeting of our supper club, The Brooklyn Food Group, the weekend before Thanksgiving.

The days before were filled with flour and yeast. Dough rose, rested, relaxed on my windowsill and kitchen table. Sugar spilled on the floor and cornmeal coated my clothes; the oven clanked constantly. Cream scalded and tempered eggs faded to pale yellow. Whisks were plentiful. And as I sat on the subway, on my hour-long commute to school the day before the event, I couldn’t shake the scent of butter.

Four days later I would stand barefoot in my mom’s kitchen in Boston, relaxed and sleepy as I casually basted turkey and slowly rolled pie dough. Thanksgiving cooking didn’t carry such a sense of urgency.

But that night—the Saturday of the supper club—my friend Ben and I spent many frenetic hours sautéing and frying in the small confines of a sweaty Brooklyn kitchen. Twenty-three guests sat—drinking, laughing, eating—at two long tables nearby; we fed them six courses.

Ben, who is now a line chef at a wonderful restaurant on the Upper West Side, outdid himself with the savory courses.

There was a nutty beige cauliflower soup with raisins agrodolce; an autumnal salad studded with purple cauliflower, farmers market apples, pumpkin vinaigrette and a knobby stack of sautéed mushrooms.

There were basil pancakes: deep green, tender, and balanced on an orange puree of chile-pumpkin. They were topped with pickled fennel and reduced orange juice syrup. And for Ben’s final course, there were freshly made cardamom noodles with a slow-roasted lamb ragu.

My contribution—aside from the baskets of Italian bread and sea-salt focaccia, which had oozed the sweet and steamy scent of “fresh baked” into my apartment all morning—was dessert.

Pumpkin Crème Brulee; milky bronze and peppered with spice. I melted the sugar sprinkled over the custards with a small blow torch. It formed a crunchy, sweet skin to be cracked with a dessert spoon for the first bite.

It was a successful night. When I got home I collapsed into bed and have perhaps never slept so well in my life.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Fall?

I noticed this yesterday morning when my computer screen became blurry with frustration and I decided to bake cookies instead. I put my Kitchenaid mixer on the windowsill and was surprised by the sudden color outside and surprised, again, by the sweet and salty smell of butter as it churned.

The night before a cold rain had pattered on my umbrella and my friend Ben made a meal of homemade pasta fragrant with cardamom and tossed with a handful of sautéed mushrooms, which tasted like October.

I suppose I knew that summer had ended. But it wasn’t until later yesterday afternoon, when I walked through the Grand Army Plaza farmers market on my way to Prospect Park and saw the piles of pumpkins and crates of knobby gourds spilling out of the stalls, that I realized that it is indeed autumn. All I wanted was apple pie.

So this afternoon I was sitting at my desk, which is covered in mounds of papers and books and rambling lists of things that I need to do, and felt overwhelmed with things to write and articles to read and interviews to schedule. So I decided to go to the grocery store. And then I decided to cook. I’m a procrastinator. What.

I didn’t make an apple pie. But it was something warm and burnished and felt like fall: vegetable and barley soup topped with a soft-poached egg.

Now, go back to work Molly.

Vegetable Barley Soup with Poached Egg

inspired by Gourmet magazine, November 2007

1 medium onion, chopped

2 garlic cloves, chopped

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 teaspoon chopped thyme

1 can diced tomatoes

1 qt vegetable stock

3/4 cup barley

6 cups spinach

1 tablespoon white vinegar

4 eggs, or one per serving

-Cook onion and garlic with a half teaspoon of salt in oil in a saucepan over medium heat. Stir every so often until pale golden, 10 minutes.

-Discard stems of mushrooms and slice thinly. Add mushrooms and thyme to onions and cook until soft, 5 minutes.

-Stir in tomatoes with their juice, stock, barley, and a half teaspoon of salt and pepper each. Simmer, covered, for 15 to 20 minutes.

-Add spinach, stir till wilted, 1 minute. Season to taste.

-Meanwhile, bring a saucepan of water to simmer with a tablespoon of vinegar.

-Break one egg at a time into separate cups, and then slide into the water, one at a time. Poach until whites are firm, 2 - 3 minutes. Transfer to paper towel, and then serve on soup.

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Holding my nose

The lack of activity in my kitchen, however, has not stopped my olfactory neurons from dancing around in my head. More scent has returned in the last two months than in the last two years combined.

And, frankly, it’s driving me insane.

It feels at times like my nose is going haywire. I’m hit by a smell—often new, sometimes indefinable—and I can’t concentrate. There are moments when I can hardly think beyond the thick, malodorous stench of a simple can of cat food.

--

A whiff of cologne on the street near my apartment stopped me in my tracks.

I opened a stiff old book at the library and its mildewed pungency sent shivers down my spine.

I sat near the water off of Hunts Point in the south Bronx, and found myself breathing through my mouth because the air smelled so briny that I felt sick.

The only thing I retained from a recent lecture on the ethics of journalism is the shower-fresh deodorant of the man next to me.

And just last night I stared at the stick of butter in my hand—still cold and in its wrapper—not believing that anything could so reek of salt and sweet cream.

--

My sense of smell is by no means fully back. Many things continue to exist purely in the textural and visual. But the world is certainly coloring itself in a different, thicker way.

And I’ve come to the conclusion that this is wholly due to my mood.

It’s been clear to me since the beginning of this whole loss-of-smell thing that the re-growth of my damaged olfactory neuron was strongly related to my memory and experience. The smells that returned first had everything to do with moments of happiness. The bad have stayed away or just slowly eked their way back into my consciousness.

And, right now, I’m happier. School is challenging. My apartment has large windows and a cat that only yowls when extremely grumpy. Fall is seeping back into the world and the newspaper’s pages crinkle just so.

If it means that sometimes I have to breathe only out of my mouth—like this afternoon, when I sat on a sunny bench in Union Square trying to read but couldn’t process anything besides the spicy scent of the pasta a woman was eating nearby—I’m OK with that. It’s rather exciting, actually.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

All That

I was there to cover a memorial service for the sixth anniversary of 9/11. St. Paul’s Chapel—just a block from Ground Zero and an hour before the ringing of church bells echoed in memory of the first plane crash—was a solemn space. A sense of quiet reflection pervaded the crowds walking past me on the street.

I waited on the sidewalk for a friend from graduate school, taking a moment to collect myself before I began this reporting assignment, and ate an apple. It was one that I bought from the Brooklyn farmer’s market last weekend, crisp and cool with a gnarly stem.

And as I ate—watching the neon-vested crossing guard wave at a little boy across the street, the women with shiny hair and tipsy black heels and the men in business suits on blackberries walk by—I remembered a line from a piece that Joan Didion wrote when, at age thirty, she decided to leave New York for L.A. She speaks about her early days in the city, just a few years after college, when she was late to meet someone but bought a peach on Lexington Avenue and stopped to eat it on the corner.

I could taste the peach and feel the soft air blowing from a subway grating on my legs and I could smell lilac and garbage and expensive perfume and I knew that it would cost something sooner or later—because I did not belong there, did not come from there—but when you are twenty-two or twenty-three, you figure that later you will have a high emotional balance, and be able to pay whatever it costs.

That essay—Goodbye to All That—lodged itself in my mind a long time ago. Joan Didion, as I have written before, is a favorite.

But right then—in front of the chapel that gave shelter to dust-covered passersby as they ran from the collapsing towers six years ago—that image of a young woman eating a peach, struck by the knowledge that there is a cost to life in New York City, resonated sharply.

Perhaps it was because, now one month into an intense graduate program of journalism, I am having more trouble than usual getting Didion out of my head. Perhaps it was because the effects of grief surrounded me, putting everything in broader focus. Or, perhaps, it was simply because I was there, on the street, eating an apple.

But, I stood there for a few minutes, waiting to begin reporting, and nothing tasted more apple than that apple, and nothing felt more New York than that damp New York sidewalk.

Friday, August 10, 2007

Cookie, Anyone?

"What's that smell?" I asked, suddenly hit by a waft of buttery sweet. "Is it some kind of baked good? Mmm ... like cake, just coming out of the oven. Kinda nutty, too. Almond biscotti!?!"

My mom looked at me oddly.

"Um, no Molly. That's skunk."

"Oh."

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Apartment; Pizza

But I am here now. And lying on the (new, wooden) floor feels best. Right next to the bright red wall which Adrienne, my new roommate, painted while I sat nearby and provided moral support, wine, and select passages from a Robert Moses biography, my current 1200 page challenge. (The wall matches my red kitchenaid mixer perfectly, which happened on purpose.)

I have relocated from Park Slope to Prospect Heights in Brooklyn. Not too far away, but closer to an express train that will zip me away to grad school (beginning in just about two weeks!) with far greater ease.

Cooking has yet to happen here. But late on Saturday night, after a long and sweaty day lugging dressers and bed frames up and down multiple sets of stairs, Adrienne and I sat in our new living room, surrounded by suitcases and boxes—she in a pink armchair and I on my rolling desk chair—and fashioned a table from some (of my many) boxes of books. I had blown through the farmer’s market early that morning to pick up some initial groceries for the new place and bought a pizza-like concoction – rosemary, roasted garlic, caramelized onions and blue cheese on a freshly baked round of bread – from a slim, tanned man with a delightful French accent. It came out in all its crusty, yeasty glory around 9pm, alongside a few frosty bottles of Brooklyn Brewery Brown Ale. I was loopy with exhaustion, covered in bruises and bumps, already stiff and sore, and could not have been happier. The chocolate ice cream that followed, spoons straight in the container, also helped.

Monday, July 16, 2007

The Best Kind of Sandwich

“I am now on the quail bandwagon,” said my brother seriously, the sleeves of his blue button-down rolled up to his elbows. A white plate so clear it could have been licked clean lay on the table in front of him; it once held a salad of pickled green tomatoes, fresh figs, and fingerling french fries underneath a seared quail breast, topped with a fried quail egg and pomegranate molasses. Coming from a guy who wouldn’t eat anything but white food (vanilla yogurt, plain pasta, etc.) for the majority of his childhood, this was big.

The business man seated across the table—distinguished gray hair and a black polo shirt; a glass of delicate rose in hand—nodded in agreement. “I don’t often like dishes that incorporate eggs like this, but it worked wonderfully.” His wife, an artist, was smiling and talking to the photographer a few seats down. I could hear an excited conversation running about a recently opened gastro-pub in Brooklyn. The apartment's light was diffuse and warm; meat sizzled behind the cobalt blue curtain separating the diners from the kitchen. Wine glasses clinked and a peel of laughter erupted from the next room over.

This past Friday was the third event of the Brooklyn Food Group, a“roving supper club” that I began with a few friends in April. Twenty-two people—a group ranging in age and profession and including my wonderfully supportive brother and two of his friends—were gathered in an apartment in Cobble Hill, partaking in our five course meal.

Ben, our chef, outdid himself with the savory courses: it began with a riff on ratatouille (red pepper puree, fried squash blossoms filled with a cinnamon ricotta, eggplant caponata); then a snapper cerviche with jicama, peach, red onion and coconut alongside a mini fish taco; a fresh pasta course with peas and pesto; and then the quail.

As pastry chef and official bread baker of the establishment, I spent a good part of last week playing with sourdough starters and cookie doughs. Fragrant loaves of Italian bread and a rosemary focaccio emerged from my oven early that morning.

But mainly, in the midst of this sweltering July weather, I could not get away from ice cream—thinking about it, making it, eating it. And what resulted was a tasting of mini ice cream sandwiches: molasses cookies with plum sorbet, saffron-butter cookies with pistachio-cardamom ice cream, chocolate wafers with fresh strawberry ice cream, and peanut butter cookies with dark chocolate ice cream.

In retrospect, creating these elaborate ice cream and cookie combinations to feed so many was perhaps a bit much and the process was not without some stress (who knew things could melt IN the freezer?). But I was proud of the end result: four little sandwiches—varying in color and texture, all contrasting a creamy cold with sweet crunch—lined up on the white plates, balanced next to a small berry salad, and popped into mouths by hand.

It was fun, successful night; it reminded me, again, of how much I love to cook and how addictive the adrenaline of the kitchen can be.

Some great photos from the event are on flickr here and here.

My favorite of the sandwiches was the saffron-butter cookie with a pistachio-cardamom ice cream. The ice cream, however, is great straight up out of the freezer.

Pistachio-Cardamom Ice Cream

adapted from Shona Crawford Poole's Ice Cream

8 tablespoons granulated sugar

1 1/2 cups evaporated milk

heaping 1/4 teaspoon freshly ground cardamom

2 oz shelled and chopped pistachio nuts

1/2 cup whipping cream

Add sugar to 1/2 cup of water in a heavy pan and heat slowly until the sugar is dissolved. Bring to a boil and cook the syrup for five minutes. Set aside to cool. Add evaported milk, cardamom, nuts, and cream.

Freeze in an ice cream maker, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Monday, July 9, 2007

I could smell my brain

I was sitting in my bed with a bottle of water and stack of books by my side. My left leg, encased in a bulky metal knee brace and layers of bandages, extended limply in front of me. My mom stood at the doorway and stared at me blankly.

“Your… brain?” She started to laugh and then stopped; she looked confused.

“I can,” I said. “It’s always there, whenever I exhale. A smell. A noxious, earthy smell.”

…

“What else could it be?” I asked, gesticulating around me. “I haven’t smelled a thing in over a month. And this… It is obviously not coming from something outside of me. So it must be from within. What else could it be but my brain?”

“I’m not sure it’s possible to smell your brain,” my dad, a doctor, said when I told him later that day. But I chose not to believe him. I liked the smell of my brain—woodsy with a slightly smoky backdrop; it reminded me of a hike I once took in Vermont in the fall, red leaves crunching underfoot.

“That’s awesome,” said my little brother, at home for a weekend from college. “My sister can smell her brain.”

“Ew.” My mom.

It had been five weeks since I was hit by a car and fractured, among other things, my skull—an injury that resulted in severed olfactory neurons and the loss of my sense of smell. Just out of knee surgery, I couldn’t walk and would be in bed for weeks. I felt wild and slightly out of control, my mind looping every which way on pain medication and my own dosage of home-grown denial. I wouldn’t let myself think about what had happened. I did not quite believe it was real.

Later, I learned that those who lose their sense of smell due to head injury often experience what are called “phantom smells”—pungent yet nonexistent scents, often foul—constantly humming in their olfactory consciousness. My brain-scent was the first of any kind I had experience since the accident and though not unpleasant, was certainly phantom. After five weeks experiencing only the heat of a once nutty coffee, the gelatin slickness of a once rich chocolate pudding, and harsh saltiness of once ripe parmesan cheese—this scent, brain or not, felt wonderful.

It lasted only a few weeks, gradually petering off and leaving me with the familiar nothingness of a scent-less world. I soon forgot about it, as I have forgotten about much of those first painful months of recovery, letting them fall quietly away to the hazy perch of repression in the back of my mind. But I was reminded of it the other day while walking down a dirt road in rural Pennsylvania with my mom on a long-weekend trip, and was suddenly hit with a pungent woodsy smell. A smoky backdrop. Someone, perhaps, had built a fire.

“Remember when I was so sure I could smell my brain?” I asked.

“Yeah,” my mom said with a little laugh. “That was weird.”

I haven’t had any phantom smells since. But barreling into the heat of this summer, I’ve started to wish that some of them were. The Second Ave subway stop on the F train? I would hope, for my companion commuters especially, that the odor that washed through the open train doors was a figment of my olfactory imagination. Unfortunately, I hear, it is not.

I’ve been hit with many new smells lately. Or if not new, with an intensity I’ve never before experienced, which sometimes border on ferocious (like the red snapper that lived in my nose for days after it was seared and consumed in my kitchen). I think part of this is simply due to the fact that I am, to be blunt, happier. In the little over a week I’ve had off since my last day of work I have experienced more new, strong smells than in the last two months combined. Cilantro hit me over the head while chopping for a salad; cantaloupe’s sweetness shimmered from five feet away; the subtle jasmine of my mug of tea poked its head into my exhale; a man’s cologne—sudden, vividly ex-boyfriend—appeared on the subway. It’s mysterious and intriguing: my mood plays a heady roll in the inner workings of my nose.

As a result, the city is changing. Last summer, only a year post-accident, New York was a blank, sunny slate. The cement sidewalks were warm; beautiful glistening people in high heels or double breasted suits strutted along Madison Avenue near my office. The breeze, as I walked through Central Park’s groups of chattering pedestrians, was warm. It was a humid, sweaty world—but one that spoke to me purely through the visual. The parks were green; the buildings were tall and shadowy, windows shiny; subways were dark and sometimes crowded; my apartment was bright and serene.

I forgot that scent changes all that. The trains, especially, are bastions of smell. Summer subway rides are rich, cloying—discomfort runs off the backs of passengers with odors that stick to my face, hair. It’s hard to shake that barrage of body, especially because its presence is as yet so unfamiliar. The parks carry a twang of smoke, whiffs of tree and flower, the liquid waft of water, drifting coal and grill, roasted nuts. The streets are filled with surprises—rotting trash! coffee beans! Even the department stores call to me with the cool scent of air-conditioning, their subtle olfactory ploy.

Often when I walk around the city, dodging tourists and business men, cars and vendors, I retreat into my mind. My mom, who does the same thing, calls it “tunnel vision”—we are oblivious to the world, lost in our thoughts. But these days I am often tugged suddenly out of my mind and into the world around me with unexpected scents—some good, some bad—but always in that moment, there. I notice more; I concentrate more.

New York—though never staid—has become a more vibrant city. This new influx of smell irks me (try smelling nothing but red snapper for two day straight), excites me (who knew the fountain in Bryant Park smells like my old summer camp?), and fills me with hope (the calm scent of a man’s deodorant, previously undetected, on a lazy Sunday afternoon.)

Monday, June 11, 2007

Spice and Time

My grandmother was perched, bird-like, on her hospital bed. In the final stages of Alzheimer's disease, she had been recently transferred to a facility near my aunt's home on the island of Kauai. She looked small and wrinkled. Confused.

I watched the speckled light hitting the floor, listened to the whispering footsteps in the hall and the chatter of nurses coming in and out of the room. It was vacation; my skin was slick with sunscreen. I had recently discovered the joys of coconut milk, the terror of jelly fish, and flowers so lusciously scented it was almost too much to wear them in a lei around my neck. I was very concerned that the purpled-toed plastic sandals (so stylish!) I had seen at a tourist shop would no longer be there when I could finally convince my mom (I need them!) to let me purchase a pair. I couldn't really understand why we were there in the room that smelled of baby powder and lemon juice, salt and old age.

"Karen?" my grandmother said in a soft, shaky voice. She was staring straight at me. Suddenly, I was terrified.

"No, Grandma…" I said. "I'm Molly."

She shook her head slowly.

I looked up at my mother beseechingly.

"Yes, Mom, this is Molly." My mother's voice was calm. "She’s my daughter; remember her? I'm Karen; I am your daughter." She put her hand warmly on my shoulder.

My grandmother was obviously confused. She looked haphazardly around the room; her gaze continued falling back on me.

"This is my daughter Karen," she said quietly, to no one in particular. She was smiling. The room was silent.

I looked up at my mother, somehow expecting her to set the record straight. I had been warned that this would be a tough visit, that my grandmother was not very lucid. But I found it difficult to believe that she thought I was her daughter. I was Molly; my mom was Karen. And this strange, fragile woman on the bed? I had very few memories of her; we had nothing in common. I knew only that her name was Marian. And that visiting her in this home near the ocean made my lips taste vaguely like salt.

My mom, however, said nothing. She looked sad.

**

I went to visit my mother in Boston for Memorial Day weekend this year. And on that Monday evening--after a full couple of days ripe with long walks and shopping trips, errands and visits to old friends--I cooked dinner. We ate outside in the hazy warmth of my mom’s well-manicured garden. It was a relaxing night before my early train ride back to New York the next morning. The fare was simple: cedar-planked salmon on the grill, fresh corn on the cob, arugula salad, and a strawberry-rhubarb pie.

I went to visit my mother in Boston for Memorial Day weekend this year. And on that Monday evening--after a full couple of days ripe with long walks and shopping trips, errands and visits to old friends--I cooked dinner. We ate outside in the hazy warmth of my mom’s well-manicured garden. It was a relaxing night before my early train ride back to New York the next morning. The fare was simple: cedar-planked salmon on the grill, fresh corn on the cob, arugula salad, and a strawberry-rhubarb pie.When I had told my mom that morning that I wanted to bake a pie, she immediately went to an old box of recipes she has stored in a cupboard.

“My mom used to make an amazing rhubarb pie,” she said. “Maybe I still have the recipe.”

“My mom used to make an amazing rhubarb pie,” she said. “Maybe I still have the recipe.”She handed me a worn index card, stained with spice and time. And in delicate cursive was my grandmother’s recipe for rhubarb pie. I was surprised to find such lovingly detailed directions; it was difficult for me to imagine the confused, deteriorating woman who I last saw in the nursing home fifteen years ago making such a pie.

But my grandmother was a good cook, my mom said. She would often have a loaf of freshly baked bread, warm from the oven, filling the house with its cozy scent for my mom and her sister when they came home from school.

The recipe was written in a very careful hand. Every 'i' was dotted perfectly, each 'y' looped with a graceful curve. It felt very personal, as if I were intruding on a private moment. Like I was holding a wispy thread of her memory - one that had floated just out of reach in the nursing home.

The recipe was written in a very careful hand. Every 'i' was dotted perfectly, each 'y' looped with a graceful curve. It felt very personal, as if I were intruding on a private moment. Like I was holding a wispy thread of her memory - one that had floated just out of reach in the nursing home.And the pie--sweet with a hint of sour, oozing pink inside a golden butter crust--was delicious.

I tweaked her recipe a bit; I added strawberries, took away some sugar. I used my own, well-practiced crust formula. We ate it in the garden, warm from the oven with vanilla ice cream.

Strawberry-Rhubarb Pie

adapted from my grandmother

Filling:

4 cups cut rhubarb

1 pint strawberries, sliced

3/4 cup sugar

1 1/2 tablespoon butter

1/3 cup flour

Crust:

2 ½ cups all-purpose flour

large pinch of salt

2 tablespoons sugar

12 tablespoons (1 ½ sticks) butter, chilled and cut into small pieces

8 tablespoons vegetable shortening, chilled and cut into small pieces

8–9 tablespoons ice water

1 egg white + 1 tablespoon water

- For the crust, mix flour, salt, and sugar in a large bowl. Add butter and shortening, mixing with a wooden spoon and then, working quickly, combine even further with the tips of your fingers until it looks like cornmeal with pea-sized chunks.

- Sprinkle all but 2 tablespoons of ice water over the mixture, gently stirring and pressing with a rubber spatula until the dough comes together into a cohesive mass. If still dry, add the last of the water. Turn dough out onto a lightly floured surface and gently knead until the dough comes completely together. Divide dough in half, form into balls, and wrap each in plastic wrap. Refrigerate at least ½ hour.

- While dough is chilling, slice rhubarb and strawberries into ½-inch pieces. Combine with sugar, and flour. Stir to coat.

- Preheat oven to 425 degrees. Unwrap one of the dough balls and, on a floured surface, roll it out into a circle two or more inches wider than the diameter of your pie pan.

- Fold the dough circle in half and then in half again to make it easy to transport. Place it in a 9” pie pan, the point of the dough triangle in the center, and unfold to cover the entire pan, with excess hanging over the lip. Gently press the dough down to eliminate air pockets underneath.

- Put the fruit mixture into the pie pan. Top with pats of butter.

- Roll out the other half of the dough into a large circle. Place on top of the pie. Trim and tuck the excess dough around the pie rim underneath itself to form a lip. Using the tines of a fork, press down the edges of the crust to make indentations and seal in the juices. On the top of the pie, cut four slits to let steam escape while baking.

- Beat the egg white and water slightly and brush the mixture over the top crust. Sprinkle with sugar.

- Bake 20 minutes (crust will be golden); then reduce the temperature to 375 degrees and bake another 30–35 minutes. Check every so often, and if the edges appear to be getting too dark, take a long, narrow piece of foil and loosely cover them.

Saturday, May 12, 2007

Two Years

It was a rainy afternoon in Providence, late in my final semester of college. I had recently finished a trial night working in the kitchen of an innovative Boston restaurant and was set on pursuing a culinary career after graduation. I planned to work my way up the line of a restaurant kitchen, starting as a dishwasher. Many thought I was crazy. I would be spending my summer knee-deep in chicken stock and piles of potato peels; I would see more towers of dirty dishes and butchered lamb carcasses than friends and family. I wanted to make sense of my experience, to record it in a pubic forum. So I sat down, began to write, and this blog was born.

A lot has happened since.

There were long nights hauling dishes and scrubbing still-sizzling sauté pans. I perfected my onion-chopping technique and peeled enough garlic to fill multiple swimming pools. I gained fifteen pounds of muscle and, as my mom said, began to resemble a line backer. I set an official start date at the Culinary Institute of America.

Then, on a drizzly morning at the end of August, I was hit by a car. I lay immobile in bed for months with a broken pelvis, sacrum, skull, and torn knee ligaments. Slowly, however, they healed. More devastating was the severed olfactory neuron and resulting loss of my sense of smell.

"The olfactory neuron is the only one in the body that will regrow," said the doctors at UConn's Taste and Smell Center, where I was tested in December of 2005. "Perhaps someday it will return." But no one really knew. There was a monotone nothingness in the space where fresh cut grass or 'new car' once resided. And taste is 80% scent; I could not perform in a professional kitchen.

Six months later, when I could walk without pain, I moved to New York City and took a job at an art magazine. I fell in love with the rich culture and the frenetic movement of the city; I worked, wrote, partied, and cooked. I continued to heal.

Smells that meant something to me came back first: chocolate, rosemary, wine. More followed in tiny, almost-imperceptible steps. Cilantro. Garlic. Laundry and soap. A year ago I had a whiff of spring. I was startled by a pile of rotting garbage. The other day I walked through Chelsea Market and was almost bowled over by the noxious smell of lobster oozing out of their seafood store.

I've learned to cook and to enjoy food despite—and because of—my struggling olfactory sense. I have a new understanding of temperature, texture, and the visual aesthetics of food. I begin at graduate school for writing in August, still here in New York.

I read through the archives of my blog this morning. I'm happy to have this record of my experience; it has been quite a couple of years. I've put together some of my favorite posts below.

The Restaurant:

A Beginning

Decapitated Sardines and Flying Sauté Pans

A Sweetbreads Overkill

The Accident:

Unexpected changes

Recovery:

Bittersweet

Salsa, Rosemary, and James Bond

The Unexpected Scent of Chocolate

New York City:

Pickle People

Tribute to Gaudi

On Returning to the Restaurant, One Year Later

Fear of Frying

And of course thank you, all, for reading.

Monday, May 7, 2007

Scoop

And so I suppose it’s not so very surprising that amidst all that change there have been other, smaller adjustments as a result. For example: my daily excursion from the office to re-caffeinate myself. Every afternoon I steal out of work and take a walk, punctuated with a large cup of coffee. In the last few weeks, however, I've often found myself strolling down Madison Avenue in midtown Manhattan not with coffee, but with an ice cream cone in hand.

The effect that ice cream has on my mood can be drastic and is a phenomenon widely noted by those close to me. Some have even suggested that there may be something wonky with my brain's wiring. Even on days where the stress of impending decisions mixed with the exhaustion that comes hand-in-hand with my Spring allergies feel like they may swallow me up whole or cause me to "inadvertently" kick the next person who gets in my way as I walk down the street, a scoop of chocolate can pull me out of my grumpy abyss to be a functional human.

There is something inherently cheerful and child-like about the act of walking down the street holding a cone. When I studied in Florence for a semester, the first thing that struck me about the city wasn't the massive Duomo or the colorful buildings overlooking the river Arno, but was the sheer number of people traipsing down the cobblestone streets with cones of gelato in hand. They weren't just tourists, not only children – but white-haired, stooped grandmothers and business men in suits, couples in love and groups of young men wearing ripped jeans and leather jackets. It was normal to walk down the street with an ice cream cone and I loved that.

And I'm not sure if my daily ice cream excursions help in the decision-making processes or stress-reduction attempts. But they are an excellent distraction (it's important to concentrate on the physics of the cone as you eat and walk, so that nothing melts onto your clothing and you don't inadvertently walk back into the office with chocolate smears on your nose) and certainly made me a more palatable individual to have in the work place.

This weekend, however, I decided that for the love of my arteries and bank account I should instigate a bit more change into this new routine. With the inspiration of David Lebovitz's cookbook "The Perfect Scoop," I made frozen yogurt. I love the tangy, slightly sour taste of plain yogurt – here it is chilled and churned with a bit of sugar. It is reason enough to transplant my daily fix from Madison Ave. to the shady stoop of my apartment. Now I just need to go to the store and buy some cones.

Plain Frozen Yogurt

loosely inspired by The Perfect Scoop, and Heidi's 101 Cookbooks

3 cups Greek yogurt (I used Fage Total)

2/3 cup sugar

Mix together the yogurt and sugar until dissolved. Refrigerate for at least an hour, and then churn in an ice cream maker, per the instructions of your specific model.

Tuesday, May 1, 2007

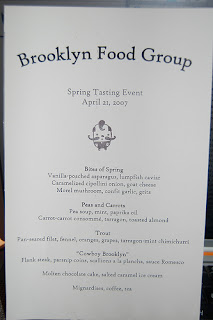

Brooklyn Food Group

Though I’ve been baking a lot of bread lately, this was the first time I had attempted any form of mass production in my tiny kitchen, in my tiny oven. And this bread was important. Sliced, piled on trays, and perched on the white linen of three long dining tables, it was the first thing the 28 guests would encounter as they arrived that night for a meeting of the “roving supper club” orchestrated by me and my friends Ben and Philissa.

Our supper club was an informal, semi-spontaneous gathering of friends—an eclectic group, of all ages and professions—who came together for an evening and an inventive five-course meal. We cooked and served in the spacious apartment of a friend. Ben - a talented self-taught chef and teacher by day - reigns over the savory while I am pastry chef. I have found that baking involves an exacting adherence to science, a precision of touch and aesthetic view; I don't need a full sense of smell to succeed.

We had been talking about beginning this supper club for a while. We had tested recipes and planned menus, debated venues and price. But despite our enthusiasm it was a large undertaking and I was not sure it would ever come to pass. But then (and what felt like suddenly) it did. Emails were sent and RSVPs taken; chairs and tables and crate loads of plates were rented. Menus were printed and tables set.

Ben played with homemade stocks, soups, and picked vegetables. He debated buffalo versus steak. Trout versus tuna. Grits and risotto. Morels and portabella. Sunchokes and ramps. I played with raspberry gelees and peppered biscotti. Ginger snaps and shortbread. Ice cream bases were created on a tipsy Friday at midnight. Fermenting bread base littered my apartment’s refrigerator.

And around 7 on that Saturday night guests began trickling in. Bearing bottles of wine they congregated in the dining room as the light slowly faded outside. Ben and I, sectioned off in the small kitchen with strategically placed tapestries, moved quickly to get everything ready to the background sound of laughter and clinking glasses.

When all twenty-eight guests had arrived and settled in, we gave a few words of welcome and introduction. People sat at the three long, white-linened tables, a menu perched at their place. It was quite a group—mainly friends and friends-of-friends, but ranged from teenage to grandmother, work colleagues and bosses to dancers and writers, comedians and bankers.

from teenage to grandmother, work colleagues and bosses to dancers and writers, comedians and bankers.

Ben and I scurried back to the kitchen to begin plating the first course. Philissa, who decorated the apartment beautifully, helped serve.

Preparing and executing all that food for so many people was wild and perhaps a bit crazy. It was a night filled with movement and hectic timing. There was a constant sense of urgency; adrenaline soared. The possibility of catastrophe lurked.

We moved quickly through the kitchen—grilling scallions, searing meats, spooning a nutty brown romesco, poaching asparagus. Bent over the white dishes lined on an overturned bookshelf, we plated each course with attentive detail. The close quarters, the heat of the oven and the constant desire for speed reminded me of when I worked in the restaurant in Boston. Time flew. Against the hum of chatter and merriment, I concentrated on the immediate sizzle and sear, steam and boil. I could feel the heat of the oven, an occasional flash of burn on my hands as I grabbed pots and pans, the weight of plates in my hands as I brought them out to the smiling eaters.

Later, guests said that they had no idea how hectic it was in the kitchen. They just registered the calm presentation of food, in evenly-spaced courses. And that was the point, I suppose. Just as when I worked in that Boston kitchen, the steaming speed of the grill line and the Chef, the yelling and the slamming of sauté pans was a world so far removed from the dining room only three feet away. Adrenaline propels the food to its calm destination.

The first course, “Bites of Spring”, was a plate containing three small creations. Vanilla-poached asparagus on toast with lumpish caviar; a caramelized cipollini onion topped with goat cheese and a spiced pistachio; a sautéed morel mushroom filled with confit garlic grits.

Then came “peas and carrots”: two small bowls, one of pea soup with mint and paprika oil, the other of carrot-carrot consommé with tarragon and toasted almonds. A slice of oozing grilled cheese sat in between.

Next was a seared filet of trout balanced on a salad of fennel, orange, grape, and tarragon-mint chimichurri.

Then, slices of flank steak were laid over parsnip coins, grilled scallions a la plancha, a dollop of a rich and bronze sauce romesco, a dollop of pickled red onions on top.

For dessert were individual molten chocolate cakes nestled in ramekins, a scoop of salted caramel ice cream by its side. I was very proud -- when the piping hot cakes arrived at the tables there were quiet moans of pleasure. Later, with tea and coffee, came plates of ginger snaps and lemon shortbread.

Later we went to a nearby bar to decompress and celebrate. It was a day that began with a herd of bread and ended with a round of toasts.

*check out onenicething's flickr page for some beautiful photos!

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Bread Bender

It was a time rife with solitude. The days were long, with my mom at work and my friends scattered around the world. I was largely alone; it was easy to imagine that no one had ever felt so shattered.

I read Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking straight through in one rust-colored afternoon. She wrote it in the year after her husband’s sudden death, while their only child was severely ill. It is a narrative of her grief, written in language simple yet utterly evocative. Her “magical thinking” came in the vice of believing her dead husband would return, just as I—lying there with a long noxious bruise running down the side of my face and neck, monotone nothingness where my sense of smell once was— believed that my life would be the same once I could move again. As I read, I didn’t feel so alone.

Those months of recovery feel like a very long time ago looking back, though it was only a year and a half. Now, amid the oft-overwhelming clutter and crowd, the fast-paced movement of my life in New York, solitude is something I miss. I’ve never been good at finding the median.

But when I saw that Joan Didion had turned her book into a play, with Vanessa Redgrave playing the author, I immediately bought myself a ticket. I took myself alone on a Monday night after work.

It is a one-woman production: Vanessa Redgrave sits majestically in a wooden chair alone on stage for an hour and a half monologue. Her voice is rich, melodious. Her white hair pulled simply back from a chiseled face. She embodies the language of Joan Didion perfectly. I sat in the back corner of the dark theater, and found myself struck with memories of when I first read the book, in that time surrounding the accident. Things I hadn’t thought of in a long time.

At one point, Didion/Redgrave speaks of being with her very-sick daughter in the hospital. She wanted nothing more than to take her back to the hotel, to sit by the pool and get manicures together, to have her daughter’s hair washed in the salon. Then, at least, she would be doing something concrete to take care of her.

I suddenly remembered my own mother, who, soon after I returned from the hospital last year, brought me to the salon to have my hair washed. My body ached as they rinsed last vestiges of the accident off my skull. It hurt my broken pelvis to sit in their hard plastic chairs. I didn’t want to tell my mom, though; she was taking care of me.

When I left the theater that night I was immediately surrounded by the neon lights and the raucous throngs of people in Times Square – the night air felt stale and my shoes were cutting into my heels. But despite that, I took a deep breath and felt, for the first time in a while, that I had given myself the time and space to process what was going on around me, undistracted by people or work.

It is easy to get caught up in the ferocious movement of New York City. But ever since seeing the play I have been actively trying to give myself more space.

And this is my meandering transition to the culinary. As part of my “more time to think” campaign, I have been on a serious bread-baking bender.

There is no hurrying bread. Baking forces me to slow down; I take my time in the kitchen. On Saturday mornings, when I haul out my Kitchenaid mixer, my apartment is filled with light. The yeast bubbles softly in warm water before I add flour. The dough goes from sticky to supple as I knead it on my counter. My mixer is bright red and my apron has three little buttons the same shade of brown as the rising dough. The oven is warm and the tea kettle leaves a faint mark of steam on the nearby window. The corners of the bread pan are perfectly pointed. I let my mind wander.

And as the bread bakes my apartment is filled with a nutty, sweet perfume. It is a scent that my ravaged olfactory neuron can now detect—perhaps not in its entirety, but enough to feel its coziness.

Peter Berley’s recipe for a plain, white loaf was my most recent success.

Basic Yeast Bread: The Straight Method

Adapted from Peter Berley’s The Modern Vegetarian Kitchen

1 teaspoon active dry yeast

1 1/3 cup lukewarm water

1 teaspoon honey

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 teaspoons salt

3⁄4 cup whole wheat flour

3 cups white, unbleached bread flour

1. In a large bowl, combine yeast, water, and sugar. Stir to blend and let stand until foamy, about 5 minutes. Stir in oil and salt.

2. Add all of the whole-wheat flour and enough of the white flour to form a ragged mass of dough. Scoop out onto a clean, lightly floured surface. Wash out the bowl and clean and dry your hands.

3. Knead for 10 minutes, until smooth and elastic

4. Lightly coat the inside of the bowl with oil. Turn the dough over several times in the bowl and cover tightly with plastic wrap

5. Refrigerate the dough for at least 12, up to 48 hours

6. Remove the dough and let come to room temperature, about two hours

7. To shape the dough, gently press into 1-inch-thick circle. Fold down the top third and up the bottom third, pressing the seam together with fingers. Place in a lightly greased bread pan seam side down. Cover with damp towel. Let sit one hour, until has risen a bit more.

8. Uncover and brush with oil or a bit of melted butter.

9. Bake for 45 minutes at 400 degrees. When it comes out, a thermometer stuck to its center should read 200.

10. Let cool before slicing

Saturday, March 10, 2007

Toast to Onion Soup

I was on my way to Ann Arbor to visit Becca for the weekend. My flight, however, was delayed for three hours due to the confusion of an “illegal flight attendant.” There was a cacophony of screaming babies, constant robotic announcements on the loudspeaker, and a middle-aged woman wearing a pink velvet track suit—obviously drunk—wandering back and forth in front of me, slurred and muddled and trying to find men with whom to flirt. My time spent waiting, curled up in a hard plastic chair near the window, didn’t bother me though. (Shocking, I know, as I tend towards grumpiness). But I was too lost in my book.

Nigel Slater writes about his childhood in poignant, culinary-centric vignettes. His language is simple yet descriptive, his voice captivating. It is, after all, the narrative behind food that I am most interested in.

On the first page he writes: It is impossible not to love someone who makes toast for you.

And sitting by the gate—a mug of airport-style tea (weak) and packet of Skittles (hate the purple ones) by my side—I thought about toast. My mom used to make it for me when I got home from school slathered in butter with a sprinkling of cinnamon and sugar on top. I loved its warm crunch. I had forgotten about that.

With the topic of childhood food I am often bogged down with unctuous memories of take-out Chinese, Dominos pizza, and frozen TV-dinners. But reading Mr. Slater’s lyrical book reminded me of the other moments. And as I waited for my flight, actively avoiding eye contact with pink-velvet drunk lady and moving the pages of Toast at a rapid clip, I kept my little moleskin notebook flapped open on my lap and found myself taking notes on childhood food.

My mom made a killer meatloaf. I always watched her in awe as her bare hands squished the gurgling raw meat mixture together in a big metal bowl before molding it into a log to bake. It was topped with a red river of Heinz ketchup.

I loved the plop of bread hitting the cinnamon-speckled egg mixture while she prepared French toast; my preschool teachers used to say that every day I came to school smelling of maple syrup.

Her strawberry rhubarb pie was bronzed and crusty, the deep red innards succulent. And the huge, chocolate-pecan “whopper” cookies—still made every year without fail—are to this day lengthy topics of conversation among my high school friends, especially around Christmas time.

The best, however, was onion soup. Every year, smack in the dead of the New England winter, mom would break out the special ‘onion soup bowls’—ceramic with squat little handles and the deep hue of chocolate. And the soup: slow cooked and filled with the earthy, brothy brown of caramelized onion, topped with French bread and oozing broiled cheese. The scent of onion soup signaled school’s winter vacation, sleds skidding down the hill of my backyard, my dad building fires in the fireplace, puffy jackets and itchy hats, icy wind on my face as I went skiing with my little brother. I had forgotten about that soup; I wonder where those bowls are now.

When I was a sophomore in high school my parents divorced and there was not much onion soup – or much cooking of any kind, for that matter – afterwards. How fitting then, I thought with a smile as the nasally voice of the flight attendant suddenly began to prepare us for boarding, that while I was visiting home for Presidents Day Weekend my mom and I made onion soup. With a recipe from Nigel Slater’s own cookbook, The Kitchen Diaries, even.

The soup was easy to make, nothing like my mom’s classic and lengthy previous undertakings. But after a long walk in Boston’s bitter cold (the wind had cut through my hat; even my hair felt numb) it was perfect. We cooked together in her cozy, warmly lit kitchen. And as I sliced the crusty baguette for the topping, I could smell the earthy sizzle of the onions roasting in the oven. I could smell the rich salt of the butter melting in the pan and the nutty gruyere I grated on the counter. There isn’t much I can’t smell, at least a little bit, these days. And this soup carried a definitive scent of school vacation.

By the time I actually boarded the plane in LaGuardia that Friday I was exhausted. I fell into a mottled sleep as soon as I sat down and didn’t fully wake up until I arrived in Detroit in the early hours of Saturday morning. The intoxicated lady in pink velvet was tired as well. I know this because the gods of air travel seated her right next to me. She, too, slept the entire flight. Often with her head lolling about on my shoulder.

Nigel Slater's "Onion Soup without Tears"

adapted from The Kitchen Diaries

4 medium onions

3 tablespoons of butter

a glass of white wine

6 cups vegetable stock

1 small French loaf, or baguette

grated Gruyere, about 1.5 cups

Preheat the oven to 400F. Peel the onions and then cut them in half from tip to root; lay them in a roasting pan and add the butter, salt and some pepper. Roast until soft and tender, with some dark spots. Cut them into thick segments and put into a saucepan with wine and bring to a boil. Let the wine bubble until almost gone and then add the stock. Simmer for 20 minutes. Just before serving, cut the bread into slices and toast lightly on one side under the broiler. Remove and top with grated cheese. Ladle soup into bowls and then float the crouton on top. Place bowls under the broiler until the cheese melts. Eat immediately.

Sunday, February 11, 2007

Fear of Frying

Everything about them repulsed me—the jiggling soft piles of scrambled yellow curds, the taut cracked shell lying in the garbage can, the slimy glug of a raw yolk separating from its white. Just the plop and sizzle of an egg frying in a pan sent shivers of disgust through my body.

This passionate dislike came upon me suddenly, vehemently, and lasted in some form or another for four years. Many thought it was odd; I had no bad egg experiences, no food poisoning or salmonella. I liked eggs just fine when I left for Namibia, but not when I came home.

During my time in Africa I lived with a family in a small, poverty-stricken Namibian community. I spent my days teaching English and AIDS awareness to 6th graders and my evenings attempting to connect with my ‘host-mother’ Mbula, a woman of only twenty-three.

The village was tucked away at the end of the Caprivi Strip, a thin piece of land jutting off the larger mass of Namibia straight into the heart of Africa and 8 hours away from the closest city. In a swirling mass of dust and heat, it was an unlikely society sprung of the Kalahari Desert. Dull brown sand covered every inch of the ground; gnarled shrubs emerged impossibly from the earth; small block houses interspersed with reed huts clustered along grainy roads and charred communal fire-pits. My skin sucked up the monotone color palette; even the sky felt brown.

The gaps in Mbula and my value systems were profound and similarities few and far between. We did bond, however, over the domestic. Mbula, who had luminous black skin and was often decked in a bright green wrap-around skirt, was terrified I would never find a husband unless I could cook, clean, and sew like a true Namibian woman. She taught me to sew (I can still reattach buttons very well) and wash my clothes in their laundry bucket (launching into fits of giggles when the bar of soap continuously slipped from my hand and disappeared behind the submerged washboard). She showed me how to make shima, the potato-shaped patties of boiled maize meal, which we ate for every lunch and dinner along with gnarly sautéed greens and the occasional gristle of unidentified meat. And every morning at 5am, as the sun crept up in the lambent desert sky, Mbula and I stood together in the kitchen and fried eggs for breakfast before going to school.

Each morning as I stood over the sizzling eggs, I tried to control my lurking but severe feelings of anxiety—an anxiety that I somehow managed to supplant into all eggs everywhere. Teaching was an exercise in control—control of the 40-odd children who piled in each of my classes and of the panic I felt knowing the little time and resources I had in my school. Between the ages of 7 and 15, my students were loveable and enthusiastic, scruffy and haphazardly dressed. They looked at me with wide, often confused eyes. My American accent made English, the country’s official language, sound as foreign as their local tribal dialects did to me.

In addition, a silent haze of disease hovered over the village. Over half of the population was infected with HIV or AIDS, higher than any other Namibian town at the time. Wandering through the village on a Sunday morning, I watched men crawl out of the bars onto the sides of the streets before passing out, intoxicated by 10am; I passed lithe young women carrying sacks of grains, wrinkled grandfathers butchering raw meat in the market, and children kicking a soccer ball in the nearby sand-field. Statistically, every other person I encountered was infected. It was hardly ever spoken of; the stigma of AIDS was a constant challenge to broach. I felt always helpless, always overwhelmed. It was difficult to grow so close to my students and my host family and watch them stew in this culture of desperation; their lives so contained in a stagnant town. It was so easy to feel numb.

And when I came home, ready for my junior year of college, I didn’t talk about it. I very soon moved to Italy to study art in Florence for a semester. I thought about Michelangelo and Fra Angelico, Provelone and Prosciutto, Chianti and Umbria. But I would not let myself think about my students—certainly not Mpunga, who always sat in the front row and wanted to be an astronaut; or Rose, a sweet seventeen-year-old girl who couldn’t stop giggling when we practiced how to use a condom on a banana in my Health Education club. I did not think about the other teachers there who were sick, possibly dying; or the way Mbula sometimes sat on the couch for hours at night, staring into space with no lights on.

Instead, I developed a hatred for eggs.

But over time, I’ve been able to talk about my experience in Namibia. I’ve gained some perspective and some understanding. And I'm happy to say that, in the last year, eggs have slowly come back into my life.

First they were scrambled, with some toast. Then poached, on asparagus. Their texture ceased to disturb me and I could separate the whites from the yolk between my fingers without cringing. I may even, on occasion, have found the vivid yellow of a yolk to be quite pretty, really.

And this weekend I made the ultimate break through. I fried an egg. (Two, in fact.) Then I ate them. And they weren’t half bad.

Adrienne came over to my apartment on Friday after a long week of work, bearing the promise of weekend cheer and a bottle of wine. It was on the late end of things and I was tired; I didn’t want to cook something complicated or long winded. And so I was very happy to whip up two easy recipes from this past week’s New York Times: Garlicky Swiss Chard and Buttery Polenta with Parmesan and Olive Oil Fried Eggs. It shocked me that I had such a burning desire for a fried egg, the last vestige of my African egg-phobia, but I hadn’t been able to get the recipe out of my head since I had read it on Wednesday.

It wasn’t the best thing I’ve ever made. I couldn’t find regular polenta in the grocery story near my apartment and so gambled with the (slightly grainy, mealy) instant variety. The swiss chard could have used a bit more time in the pan and the eggs, perhaps a little less.

But that is beside the point. It is a comfy, warming meal, especially when eaten with a good friend on a chilly winter night. And I was happy, because as much fun as repressed emotions are when taken straight up, they are far more delicious fried in olive oil.

Sunday, February 4, 2007

Artistic Expedition

There was a biting wind on Saturday morning as we walked up Fifth Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. My face was numb, eyes watering despite the wool hat and thick burgundy scarf wrapped around my neck. My mom and her boyfriend Charley were visiting for the weekend and when we decided to meander our way up to the Neue Galerie on foot, we had not bargained on the wind-tunnel created by the tree-lined expanse of Central Park to our left. I was in the process of fighting off a head-cold and spent a good deal of the walk distracted by the tickling of impending sneezes, failing at all attempts to wiggle the hunk of ice previously known as my nose.

When we stepped into the Neue Galerie—a distinguished building on the corner of 86th and 5th—the toasty warmth immediately fogged up my glasses and I was blind on top of numb, wondering why I had ever wished for winter to come more quickly. But when my vision cleared and feeling beginning to re-enter my appendages, I found myself in a delightful little museum—soft light and wrought iron railings on the stone staircase.

The Neue Galerie garnered attention recently when Ronald S. Lauder (ardent collector and son of cosmetics mogul Estee Lauder) paid a record sum ($135 million) to buy Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I for the museum (his museum; he bought it in 1994). I had never been there before but have always loved Klimt’s work, and so in planning my mom and Charley’s visit, it was first on my (long, ambitious) list of places to go, amidst the (long, ambitious) list of art to see.

Klimt, a Viennese artist from the early 1900’s, is known for his many paintings and portraits of women – graceful, exotic women painted with both an elegant whimsy and romance – with elements of myth and classics, often eroticism. And Adele Bloch-Bauer is beautiful. I stood in front of the portrait, located in a small room with dark wood walls while people with audio guides clasped to their ears moved quietly around me. Her face is smooth and expressive; her hair is dark, eyes piercing. She is swathed in a long patterned gown, melting down the canvas studded in sparkling gold and colorful shapes.

Standing there I suddenly remembered a postcard I used to have taped to the wall near the desk in my childhood bedroom. It was another Klimt image, one that I had not thought about in a long time. In Lady with Hat and Feather Boa a woman with flamboyant curly hair and pale skin gazes demurely out from under a black fur hat, a dark scarf wrapped around her neck. She looked to me like she was going somewhere; the tilt of her eyes implied she was perhaps hiding something. I liked that, I remember, because I often wanted to be going somewhere myself, wishing I had something to hide behind my own eyes. And so I taped her up on the wall; I liked to think that she was watching me.

Lost in my thoughts, I jumped when my mom tapped me on the shoulder.

“Should we find a place for lunch next?” she asked with a playful little smile. “You’re in charge, Ms. Tour Guide.”

“Sure,” I said. Wracking my brain for nearby restaurants, not very familiar with the restaurants in the ‘Museum Mile’ where we were; I was annoyed (and surprised) with myself that I had not already planned where we were going to eat.

But then it came to me: the sound of clinking china as we had entered the museum, a warm food-smell (yes, I can smell cooking food from a distance!), and something that had piqued my curiosity when I read a little while ago suddenly emerged from a forgotten recess in my brain. There is a place to eat right in the Neue Galerie – Café Sabarsky, a Viennese café right standing under our feet.

We sat at a small, marble-topped table in the corner of the bright dining room. A piano stood off to the side, smartly-dressed waiters with white aprons tied around their wastes carried shiny trays holding steaming cups of coffee, a tall glass cabinet behind me held dark cakes and light strudels.

“They have sausage!” said Charley with an almost boyish delight, looking at the menu in front of him. “This is so exciting. I love German-Austrian food like this; it’s the best!” He immediately launched into an impassioned attempt to persuade my mom to order a sausage dish as well… “so I can taste more than one!” he pleaded. She was not to be convinced, however.

My mom’s family is from Denmark and she grew up loving foods and certain familiar tastes that are relatively foreign to me now. But for her, they immediately bring back memories of her father (whom I never met, but have heard much about his passion for the kitchen – a love of food is genetic, perhaps?). Pickled herring is one. It had been a while, but always a favorite flavor. After all, she told me in a confiding tone, when she lived in New York City in her late-twenties, she subsisted on only three food groups: pickled herring, cherry vanilla yogurt, and ring-dings. This confession left me shocked into momentary silence (not all food preferences are genetic, I hope?).

But my mom let Charley enjoy his pale-white Bavarian sausage with potato salad on his own, while she ordered an open faced Matjes Herring sandwich with egg, apple, and topped with thin slices of red onion.

“This is my father,” she said, multiple times, smiling as she ate. “It reminds me so much of him…”

“This reminds me of my father, too,” said Charley, gesturing at the unadorned sausages on his plate. My mom started giggling, raising her eyebrows. She's a psychoanalyst; Charley rolled his eyes. “Oh and what would your colleagues have to say about that?” he asked, laughing. I put my hands over my eyes and groaned, lamenting the sense of humor brought out with a bottle of lunch-time red wine and the insuing conversation about certain elements of Viennese cuisine.

I concentrated on my food: a squash soup – thick and vibrantly orange, topped with the crunch of green toasted pumpkin seeds – and a beautiful salad with greens, cornichons and radishes, dressed with a pumpkinseed oil vinaigrette. Charley’s chestnut soup “Viennese Melange” with Armagnac prunes was rich and sweetly nutty.

For dessert we had a Sachertorte and three forks. The sweet, dark chocolate cake with apricot confiture is a classic Viennese dessert and came with a puffy cloud of whipped cream.

We left full, warm, and a little bit tipsy. It was the perfect state to be in on a beautiful weekend afternoon in New York. Art and food each have the ability to bring back such strong sensory memories; I love experiences when they combine. And after ours, we were ready to face the cold and continue on our artistic expedition.